There is a certain moment when the reader is already half through Richard Ford’s novel Canada, when Dell Parsons, the narrator of the story gives us an insight into his philosophy of life:

“It’s been my habit of mind, over these years, to understand that every situation in which human beings are involved can be turned on its head. Everything someone assures me to be true might not be. Every pillar of belief the world rests on may or may not be about to explode. Most things don’t stay the way they are very long. Knowing this, however, has not made me cynical. Cynical means believing that good isn’t possible; and I know for a fact that good is. I simply take nothing for granted and try to be ready for the change that’s soon to come.”

What if Dell’s and his twin sister Berner’s parents hadn’t met at all? They could have married someone else, someone more suitable as a partner. What if Dell’s mother had decided to leave her husband with the children at a moment when it still was possible? She was only 34, and her husband 37 – a mismatch if there ever was one – when the terrible thing happened that left such a mark on Dell and destroyed this quite average American family, living in a quiet, average town, Great Falls, Montana. What if Dell’s father, a war hero, charming and good-looking, but obviously over-estimating his talents and under-estimating the risks of his fraudulent business schemes in which some Indians were involved, would have remained in the airforce? Probably none of the terrible events that happened, would have happened at all. But because of a tragic coincidence of many small events and happenstances, Dell Parsons has to begin the life story we are reading with the words:

“First, I’ll tell about the robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later. The robbery is the more important part, since it served to set my and my sister’s lives on the courses they eventually followed. Nothing would make complete sense without that being told first.”

What follows is the very detailed account of the events that led to the robbery and that make roughly half of the book. The amateurish bank robbery of Dell’s and Berner’s parents happened in a moment when the mother had (almost) made up her mind to leave her husband. But beside from having pretentions regarding her children’s education and of having a real talent to be a poet and writer, a talent that is suffocated in her marriage with a man from an Alabama backwater town who speaks in a funny Dixie accent that is kind of repelling for the daughter of educated Jewish immigrants – beside from that Neeva, the mother, is also a weak person that shies away in the last moment from leaving Bev, her husband.

Deep inside the mother must have felt that the bank robbery she is about to commit with her husband in order to pay a debt to some Indian who threatened to kill the family – a result of the failed dealings of her husband and his fellow crooks – is going to fail, because she made arrangements for her children to be taken to Canada by her friend Mildred Remlinger, and thus to prevent them from being brought up in a foster home or even a juvenile prison. While Berner runs away on her own and leads later a hippie-style life in San Francisco, Dell is making the journey to Canada with Mildred. Mildred has a brother in Canada, Arthur, and this Arthur is supposed to take care of Dell.

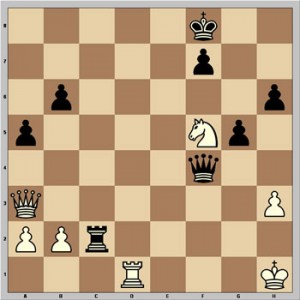

If it wouldn’t be for the intro of the book, we as readers would suspect that after the traumatic experience with his parents who are locked away for life or at least a very long time, Dell is now through the worst part of his life, and the second part would describe how he builds up a new better life in Canada. But – there is Arthur Remlinger, handsome, intelligent, with good manners, a former Harvard student, a reader and chess player with an interesting ladyfriend, Florence, a painter.

Remlinger seems oddly out of place in the godforsaken place in Sasketchewan where he owns a run-down hotel with a gambling den and a bar full of “Filipino” girls that spend the night frequently with the guests in their rooms; his right-hand man Charley, a halfbred, is a really creepy guy and probably a pervert, as Dell suspects who has to work with this Charley when the “sports”, the hunters from the U.S., visit the area that is full of game. Arthur Remlinger, an American like Dell, has a dark past, a past that is not forgotten by everyone as it turns out…and he has a violent temper too…

The reviewers were divided regarding the qualities of this book. While some praised the work as a masterpiece, others complained about the slowness with which the story builds up and about certain redundancies. Yes, this is a story that builds up very slowly – and you need to like that if you want to enjoy the novel. And yes, there are redundancies, but I found them quite interesting. After all, we are reading the story told by Dell Parsosns, after his retirement as a teacher in Canada, and after having met his twin sister again who is suffering from the final stages of cancer. For me the redundancies are attempts of the narrator to rationalize what has happened to him, to make sense of a life in which everything went upside down more than once, and to reassure himself that the things really happened to him the way they did.

What makes the book also interesting to me, are the antagonisms on various levels: between the parents; between the parents and children; between Dell and Berner, who although being twins are so different; between men and women; between the United States and Canada, so near and similar, and yet so different countries and societies. And the big villain of the book, the enigmatic Arthur Remlinger, has the format of Kurtz, the “hero” of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

How come Dell survives the catastrophes of his life so (seemingly) unharmed? Maybe it is because of his ability to take life like it is, and not as it should be according to our plans and pretentions; maybe because of the fact that he felt always loved by his parents and his sister, despite the fact that this family was not like other families; maybe because of the fact that there was always a woman in his life who made an important decision for him in a crucial moment (his mother; his sister; Mildred; Florence; Clare) that proved to be life-altering in a positive way. But in the end, it remains a mystery why some of us not only survive difficult childhoods but do something meaningful with their lives, while others in similar conditions turn into criminals or end in suicide.

Dell has not become a beekeeper, something he wanted to become when he was young; and he has also not become a strong chess player, despite the fact that he studied Mikhail Tal’s combinations again and again when he was young. But he took a few good lessons from life and mastered it somehow, even when the odds were against him in his youth, and even when his father and later Arthur Remlinger tried to make him an accomplice to their crimes.

For me this is the best work of Ford so far – and his previous books were already excellent. Canada is a book about the fragility and loneliness of life, and how to come to terms with this fact. It left a very strong impression on me.

Richard Ford: Canada, Bloomsbury, London 2012

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter