In my latest blog post, I gave an overview regarding some of the translated Bulgarian authors and their works. If you want to have a bit more background information about contemporary authors from Bulgaria, I would recommend you to have a look at the website Contemporary Bulgarian Writers.

The Elizabeth Kostova Foundation is since years successfully supporting particularly the translation and publication of books by contemporary Bulgarian authors, and the website is also a result of their work. Apart from short authors’ bios, there are plenty of translation samples that will for sure be a useful starting point not only for publishers, but also for readers. The English-language Bulgarian journal Vagabond (a well-written and edited periodical for anyone with an interest in Bulgaria) publishes in every new edition a story or a chapter of a novel by a contemporary Bulgarian author. So there are now quite a lot of accessible media that can tease the curiosity of readers for Bulgarian literature.

Although the main focus of this first Bulgarian Literature Month 2016 is on the works of contemporary Bulgarian language authors, I want to be not too strict. Also non-fiction works by Bulgarian authors can be included. The same goes for works by Bulgarian-born authors that write in another language than Bulgarian. I am even open for reviews of books (fiction or non-fiction) by foreign language authors that are related to Bulgaria.

Here are a few recommendations for all above mentioned categories:

Bulgarian-born authors that write in other languages:

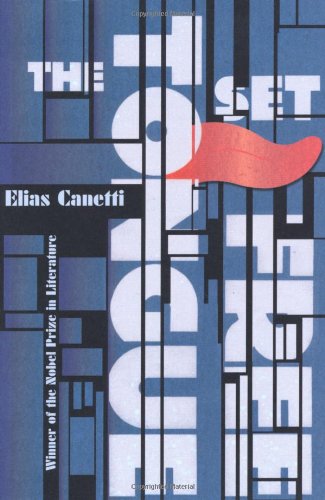

The only Bulgarian-born author that was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature was Elias Canetti. Canetti’s only link with Bulgaria is his birth in Ruse and the first years of his early childhood he spent there, and which had nevertheless a strong lifelong impact on him. More on his childhood in the first volume of his brilliant autobiography:

The Tongue Set Free (Granta Books 2011)

Some time ago, I reviewed the debut of Miroslav Penkov, his story collection East of the West, enthusiastically. The English-language author Penkov has now published his first novel, again focused on Bulgaria and similarly enticing:

Stork Mountain (Farrar, Straus , and Giroux 2016)

Kapka Kassabova, another English-language author with Bulgarian roots, left the country of her birth in 1991. Many years later, she came back for a longer visit and her impressions there brought back a lot of mostly not very pleasant memories. A somewhat controversial book, not liked by everyone in Bulgaria, but definitely an interesting read about the difficult process of transition which is still going on 25 years after the fall of communism:

Street Without a Name: Childhood and Other Misadventures in Bulgaria (Skyhorse Publishing 2009)

One of the most prolific contemporary German-language authors is Ilija Trojanow (sometimes transcribed as Iliya Troyanov in English). Of his so far translated works I recommend particularly the following books:

Along the Ganges (Haus Publishing 2005)

Mumbai to Mecca (Haus Publishing 2007)

The Collector of Worlds (Haus Publishing 2008)

The Lamentations of Zeno (Verso 2016)

Together with the photographer Christian Muhrbeck, Trojanow published an impressive book with photos from Bulgaria:

Wo Orpheus begraben liegt (Carl Hanser 2013) – this book, as all other works of Trojanow related to Bulgaria, are still not translated in English

Unfortunately Dimitre Dinev’s books, written in German, are so far also not translated in English. His touching and brilliantly written novel about two families is one of my favourite books:

Engelszungen (“Angel’s Tongues”) (Deuticke 2003)

Several other Bulgarian-born authors write also in German. I can recommend (this so far untranslated book) particularly:

Rumjana Zacharieva: Transitvisum fürs Leben (Horlemann 2012)

Bulgaria is also a topic in the work of a few fictional works by authors that have no connection by birth with this country:

Many of Eric Ambler’s books have a story that is located in some frequently not precisely named Balkan country. The following two books of this fantastic author have a Bulgarian setting (the first one partly, the second one is clearly based on the show trial in Bulgaria in the aftermath of the Communist takeover):

The Mask of Dimitrios (in the United States published as A Coffin for Dimitrios) (various editions)

Judgment on Deltchev (Vintage 2002)

Another author who is using the twilight of the Balkans as a setting for his spy novels is Alan Furst. Bulgaria features for example in the following book:

Night Soldiers (Random House 2002)

Two remarkable novels by younger international authors who spent a longer time in Bulgaria and who received excellent reviews (especially the second one, which was published recently has caused really raving write-ups in all major literary journals and even the mainstream media):

Rana Dasgupta: Solo (Marriner Books 2012)

Garth Greenwell: What Belongs to You (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 2016)

Julian Barnes visited Bulgaria after the transition and witnessed the trial of Todor Zhivkov. His novel based on this experience is worth reading:

The Porcupine (Vintage 2009)

Two historical novels by men who lived or live in Bulgaria. I haven’t read them yet, but the synopsis sounds interesting in both cases:

Christopher Buxton: Far from the Danube (Kronos 2006)

Ellis Shuman: Valley of the Thracians (Create Space 2013)

A few more books by German authors that have a Bulgarian setting and that I enjoyed (with the exception of Apostoloff, but maybe you think otherwise). Only the book by Lewitscharoff is translated so far.

Michael Buselmeier: Hundezeiten (Wunderhorn 1999)

Nicki Pawlow: Der bulgarische Arzt (Langen-Müller 2014)

Roumen M. Evert: Die Immigrantin (Dittrich 2009)

Uwe Kolbe: Thrakische Spiele (Nymphenburger 2005)

Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Apostoloff (Suhrkamp 2010)

Angelika Schrobsdorff (also known as an actress and wife of Claude Lanzmann) came 1938 to Bulgaria as a Jewish child from Germany and stayed there until 1947. Several of her works are based on her experience in Bulgaria or on her attempts to re-connect with friends and relatives at a later stage:

Die Reise nach Sofia (dtv 1983, introduction by Simone de Beauvoir)

Grandhotel Bulgaria (dtv 1997)

And finally some non-fiction recommendations:

The Bulgarian journalist and author Georgi Markov was one of the most prominent dissidents and victim of a so-called “umbrella murder”. The following book is the result of years of investigation and gives an extremely interesting insight into the real power central of communist Bulgaria, the State Security:

Hristo Hristov: Kill the Wanderer (Gutenberg 2013)

Works of Georgi Markov is available in a three-volume edition in German:

Das Portrait meines Doppelgängers (Wieser 2010)

Die Frauen von Warschau (Wieser 2010)

Reportagen aus der Ferne (Wieser 2014)

In the context of the attempts of certain right-wing circles in Bulgaria to whitewash the fascist regime of Boris III from its share of responsibility in the holocaust, it is particularly useful to read the following book by Tzvetan Todorov, who is together with Julia Kristeva one of the most prominent French intellectuals of Bulgarian origin:

The Fragility of Goodness (Princeton University Press 2003)

Another very heated discussion about a particular period of Bulgarian history was the so-called Batak controversy a few years ago. Whereas in most other countries a conference about certain aspects of 19th century history would go unnoticed outside a small circle, it resulted in this case in big and very unpleasant smear campaign with involvement of Bulgarian politicians and almost all major media in the country who, either without knowing the publication or in full disregard of the content, organized a real witch hunt against a few scholars that had in the end to cancel the conference because they had to fear for their lives. The re-evaluation of certain historical myths that were in the past used to incite ethnic or religious hatred targeted at certain groups of Bulgarian citizens is still a difficult issue. A book that is documenting the Batak controversy and the historical facts behind it is available in a Bulgarian/German edition:

Martina Baleva, Ulf Brunnbauer (Hgg.): Batak kato mjasto na pametta / Batak als bulgarischer Erinnerungsort (Iztok-Zapad 2007)

A book on the history of Bulgaria may be useful for all those who dive into Bulgarian literature. Bulgarians love their history and love to discuss it with foreigners; or more precisely: the version of history they were taught in school…

R.J. Crampton: A Concise History of Bulgaria (Cambridge University Press 2006)

A fascinating book on how tobacco, its cultivation and production, shaped Bulgaria – until today, when there is still a political party that at least on the the surface mainly represents the interest of the – predominantly ethnic Turkish – tobacco farmers:

Mary C. Neuburger: Balkan Smoke (Cornell University Press 2012)

A German in Bulgaria is the subtitle of the following book, and of course I read the very interesting, insightful and sometimes funny work by Thomas Frahm (not translated in English, but at least in Bulgarian) with great interest and pleasure. Frahm is also one of the few excellent translators of Bulgarian literature (Lea Cohen, Vladimir Zarev):

Die beiden Hälften der Walnuss (Chira 2015)

And if you are planning a walk through the Balkans or a boat trip on the Danube, the following classical works should not be missing in your luggage:

Claudio Magris: Danube (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux 2008)

Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Time of Gifts/Between the Woods and the Water/The Broken Road (NYRB)

In my next blog post I will give more information on how to participate in Bulgarian Literature Month 2016. And yes, there will be also a few giveaways!

PS: The information in the two blog posts is of course not complete, and can never be. Still, I think I should include the following as well (which I have simply forgotten):

John Updike: The Bulgarian Poetess – one of Updike’s best stories, available in several of his short story collections, for example in The Early Stories, 1953-1975 (Random House 2004)

Will Buckingham: The Descent of the Lyre (Roman Books 2013) – a beautiful novel that catches the magical atmosphere of the Rhodopi mountains, the region of Orpheus, written by an author who knows Bulgaria, its history and culture very well.

Dumitru Tsepeneag: The Bulgarian Truck – a brilliant postmodernist novel by an author from neighbouring Romania (Dalkey Archive Press 2016)

The online journal Drunken Boat recently published an issue devoted to Bulgarian literature and art. A good selection and the perfect starting point for the Bulgarian Literature Month.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter