This blog post is part of the German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzie (Lizzies Literary Life) and Caroline (Beauty is a Sleeping Cat)

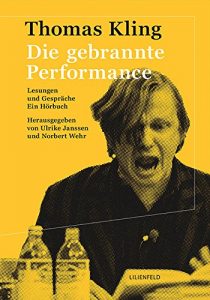

Ten years ago, the arguably most outstanding representative of this generation of German-language poets, Thomas Kling, passed away at the age of 47. With his almost encyclopedic knowledge of many subjects, including literature, history, geology and his rich language he created “poetic installations” that are particularly gripping in their polyphony when read by an experienced performer that make his poetry sound like spoken music; Kling was an impressive stage performer (a “Rampensau” as we say in German) and if you can you should look not only for a collection of his poetry, but also for a CD with poems read by himself.

As always with poetry, a translation can only give a pale reflection of the original, and many of the most elaborated poems of Kling are simply untranslatable; but I want to give at least a small impression by presenting you translations of three comparatively conventional poems by Thomas Kling (in his very special orthography):

porträt JB. fuchspelz,

humboldtstrom, tomatn(ca. ‘72)

düsseldorf, aufm schadowplatz. Eines

vormittags, im niesel. hinterm tapezier-

tisch im fuxxpelz im mantel. hab ich so

aus einiger entfernung hinter flugzetteln

gesehn; da macht ich BLAU eines vor-

mittags unter -strom(ca. ’75)

humboldtgymnasium, düsseldorf. ich sachs

euch: WIR BEKAMN HUMBOLDTSTROM. Doctor

august peters, (GESCHICHTE) zu meinem zuspät-

kommndn freund roehle: ZIEHN SIE DEN BEUYS

AUS! SEIN MANTEL WAR GEMEINT.(’77)

kassel. installation der HONIGPUMPE. ein-

leitung von sauerstoff, daß honigfluß wir

sehn konntn. mittags, vorm friderizianum

bat ich den lagerndn mann bat ich die angler-

weste um den tagschatten gibst du mir

die TOMATN und kam zu mir sein tomatnhant!From: Thomas Kling: brennstabm, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1991

portrait JB. fox fur,

humboldt current, tomatos(ca ’72)

düsseldorf, on schadow square. One

morning, in the dizzle. behind the trestle

table in a fox fur in a coat. I saw

from a distance behind leaflets;

I was skiving off one morning

under –current(’ca 75)

humboldt school, düsseldorf. I’m telling

you: we got humboldt current. Doctor

august peters, (HISTORY) to my friend roehle

who was late: TAKE OFF YOUR BEUYS!

HE MEANT HIS COAT.(’77)

kassel. HONIGPUMPE installation. in-

sertion of oxygen, so that honey stream we

could see. Afternoon, in front of fridericianum

I begged the warehousing man begged the fishing

jacket for the day’s shadow will you give me

the tomatoes and to me came his tomato hand!Translation by Noël Reumkens, Trans 8/2009

——————————————————————————–SERNER, KARLSBAD

wo in angesagter umgebun’

di zensur ihr sprudeln begann.zentralgranitmassn.

geselchter schnee. nichtswußte ich, zweiundsiebzig,

von einem haus edelweiß womattkaiserschrunde oder ocker-

gestimmte, oder sonstwi-erinnerun’:“sprich deutlicher”

in karlovy vary. . . di (mittags?)sonne, geschwächt,

in spiegeln mitgeteilt wurd; woder becherovka in geschliffenen

gläsern und rede auf di marmor-helligkeit knallte, karlsbad-sounds:

“o sprich deutlicher” in geselchtmschnee, und “jedes hauptwort ein

rundreisebillet.” SERNERder ging von prag aus

gemeinsam ins gas.From: Thomas Kling: morsch. Gedichte, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1998

SERNER, KARLSBAD

where even in posted areas

the censors babbled.tall granite masses.

smoky snow. I knewnothing, seventy-two,

about edleweiss, ocherhouses of the emperors’ realm,

or an otherwise-remembrance:“speak more clearly”

in karlovy vary.. . . the (midday?) sun, weakened,

reflected by mirrors; wherethe schnapps served in cut glass

and the talk bounced aroundthe shining marble. karlsbad sounds:

“o, speak more clearly” in smokysnow, “every noun

a round trip ticket.” SERNERwho left prague as well

headed for the gas.Translation by Peter Filkins, Poetry Magazine Oct/Nov 1998

——————————————————————————–

LARVEN

1913 sind auf Papua-Neuguinea die ströme und

gebirge längst nach den Hohenzollern benannt.

der kopf der fremde schnurrt und liefert, für neue

ferne dinge neue namen wobei die sprachn sich

vermischen, im mund der fremdes neues schmeckt

wie kopra oder kasuar. das passt zum helm. so

dampfen neue masken aus den sumpf-eiländern

auf die feierliche zunge abendland. die gaumen

segel knattern frisch ein wind aus übersee, berlin –

die zunge – erhebt als frische toteninsel sich aus

dem fiebersumpf der mark. die insel schnalzt schon

kommen worte aus der ferne. südfrüchte fallen

der stadt aus dem mund. der ist die neue zunge so

gesprächig. anders irgendwie: es sprechen alle plötzlich

wie die papuas, hofsprache iatmul. der mund als Über¬

see, als schein, so strömt der sepik mündet in den rhein.

From: Thomas Kling: Fernhandel, DuMont, Köln 1999

LARVAEIn 1913 the currents and mountains in Papua-New Guinea

are named after the Hohenzollern since a long time.the head of the foreign land hums and provides for new

distant things new names in which the languagesare mixing, in the mouth that tastes strange new things

like copra or cassowary. that fits to the helmet. Thusare steaming new masks from the swamp-islands

on the solemn tongue occident. the softpalate rattles freshly a wind from the outlands, berlin –

the tongue – rises as fresh island of the deaths fromthe fever swamp of the Mark. the island clicks already

words are coming from the distance. tropical fruits are fallingfrom the mouth of the city. the new tongue of hers is so

talkative. somehow different: suddenly everybody speakslike the papuas, court language iatmul. the mouth as over-

sea, as glow, thus streams the sepik flows into the rhine.Translation by Thomas Hübner

It would be great to see an edition of Selected Poems by this author in English!

Thomas Kling: Gesammelte Gedichte, DuMont, Köln 2006

Thomas Kling: Die gebrannte Performance, Audio Book, 4 CDs, Lilienfeld, Düsseldorf 2015

© Thomas Kling, Suhrkamp Verlag and DuMont Verlag, 1991-2006 © Peter Filkins and Poetry Magazine, 1998 © Noël Reumkens and TRANS, 2009 © Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter