This blog post is part of the German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzie (Lizzies Literary Life) and Caroline (Beauty is a Sleeping Cat)

He is probably the most important living German poet, an essayist whose publications are usually a reason for major public discussions, an author of novels, stories, plays, children’s books, a book about mathematics, several poetological books and a scholarly work on Clemens Brentano, the co-author of a poetry automaton, the editor of the famous book series Andere Bibliothek, the founder of the Kursbuch, for a long time Germany’s most important journal for political debates, and of Transit, another important journal, a film regisseur, a librettist, a congenial translator from French (Moliere, Denis Diderot, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Jean de la Varende), Italian (Franco Fortini), Spanish (Cesar Vallejo, Federico Garcia Lorca), English (William Carlos Williams, Charles Simic, Stanley Moss), Hungarian (Gyorgy Dalos), and Swedish (Lars Gustafsson), amongst others, and and and…It is impossible to write about him in a few lines.

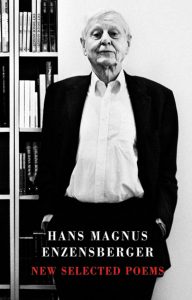

Hans Magnus Enzensberger (born 1929) is the public intellectual par excellence, a very urban and unique figure in German literature.

Fortunately quite a number of his books are available in translations, and a new poetry collection (New Selected Poems) has just been published – so maybe this is a good opportunity to discover at least the poet Enzensberger for now. Here are three exemplary poems in German and English translation:

ins lesebuch für die oberstufe

lies keine oden, mein sohn, lies die fahrpläne:

sie sind genauer. roll die seekarten auf,

eh es zu spät ist. sei wachsam, sing nicht.

der tag kommt, wo sie wieder listen ans tor

schlagen und malen den neinsagern auf die brust

zinken. lern unerkannt gehn, lern mehr als ich:

das viertel wechseln, den paß, das gesicht.

versteh dich auf den kleinen verrat,

die tägliche schmutzige rettung. nützlich

sind die enzykliken zum feueranzünden,

die manifeste: butter einzuwickeln und salz

für die wehrlosen. wut und geduld sind nötig,

in die lungen der macht zu blasen

den feinen tödlichen staub, gemahlen

von denen, die viel gelernt haben,

die genau sind, von dir.

In a College Textbook

don’t read odes, my son, read timetables:

they are more exact, unroll the sea-charts

before it is too late, be on guard, don’t sing.

the day will come again when they paste blacklists upon the door

and place their mark on the no-sayers,

learn to pass unidentified, learn more than I:

how to change your living quarters, passport, face.

understand the small betrayal,

the sordid daily escape, useful

are the wide-spread fire starters,

the manifestoes: wrapped-up butter and salt

for the defenseless. anger and endurance are necessary

to blow a fine deadly dust

into the lungs of power, ground up

by those such as you who have learned much

and are fastidious in their ways.

Translated by Jim Doss, Loch Raven Review, Summer 2008

—

Privilegierte Tatbestände

Es ist verboten, Personen in Brand zu stecken.

Es ist verboten, Personen in Brand zu stecken,

die im Besitz einer gültigen Aufenthaltsgenehmigung sind.

Es ist verboten, Personen in Brand zu stecken,

die sich an die gesetzlichen Bestimmungen halten und im Besitz einer gültigen Aufenthaltsgenehmigung sind.

Es ist verboten, Personen in Brand zu stecken,

von denen nicht zu erwarten ist, daß sie den Bestand und die Sicherheit der Bundesrepublik Deutschland gefährden.

Es ist verboten, Personen in Brand zu stecken,

soweit sie nicht durch ihr Verhalten dazu Anlaß geben.

Es ist insbesondere auch Jugendlichen,

die angesichts mangelnder Freizeitangebote und in Unkenntnis der einschlägigen Bestimmungen sowie aufgrund von Orientierungsschwierigkeiten psychisch gefährdet sind, nicht gestattet, Personen – ohne das Ansehen der Person – in Brand zu stecken.

Es ist mit Rücksicht auf das Ansehen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Ausland davon abzuraten.

Es gehört sich nicht.

Es ist nicht üblich.

Es sollte nicht zur Regel werden.

Es muß nicht sein.

Niemand ist dazu verpflichtet.

Es darf niemandem zum Vorwurf gemacht werden,

wenn er es unterläßt, Personen in Brand zu stecken.

Jedermann genießt ein Grundrecht auf Verweigerung.

Entsprechende Anträge sind an das zuständige Ordnungsamt zu richten.

Nota bene. Wer diesen Text in eine andere Sprache überträgt, wird gebeten, an Stelle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland versuchsweise die offizielle Bezeichnung seines eigenen Landes einzusetzen. Diese Fußnote sollte auch in der Übersetzung stehen bleiben.

Privileged Facts of the Case

It is forbidden to set people on fire.

It is forbidden to set people on fire in possession

of a valid green card.

It is forbidden to set people on fire who uphold

the laws and are in possession of a valid green card.

It is forbidden to set people on fire who

are not thought to endanger the continuance

and security of the United States of America.

It is forbidden to set people on fire who do not

arouse suspicion with their behavior.

This particularly applies to youngsters who, in view

of the lack of leisure opportunities and their ignorance

of the relevant regulations or because

of difficulties in orientation are psychologically endangered,

are forbidden to set people on fire they do not respect.

In consideration of the reputation of the United States of America

abroad it is urgently advised against.

It isn’t proper.

It isn’t normal.

It shouldn’t become the rule.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

No one is obligated.

No one will be reproached if they decline

to set a person on fire.

Each enjoys a fundamental right to refuse.

Suitable applications are to be submitted

to the Municipal Office of Public Order.

Translated by Jim Doss, Loch Raven Review, Summer 2008

—

John von Neumann

1903 – 1957

Doppelkinn, Mondgesicht, leichtes Watscheln –

das muß ein Komiker sein

oder ein Generalvertreter in Teppichböden,

ein Bonvivant aus dem Rotary Club.

Aber wehe, wenn Jánsci aus Budapest

anfängt zu denken!

Unerbittlich tickt unter der Schädeldecke

sein weicher Prozessor,

ein Flimmern geht durch den Datenspeicher

und blitzartig wirft er ballistische Gleichungen aus.

Eichmann und Stalin hat er mattgesetzt

in drei Zügen: Göttingen-Cherbourg,

Cherbourg-New York, New York-Princeton.

Erster Klasse verließ er die Todeszone.

Mehr brauchte er nicht als vier Stunden Schlaf,

reichlich Schlagobers auf den Mohnstrudel

und ein paar Bankkonten in der Schweiz.

Auch wer nie von ihm gehört hat

(und das sind die meisten),

der setzt mit der Maus in der Hand

seine Schaltalgebra in Gang.

Und was die Künstliche Intelligenz betrifft –

ohne die seinige wäre sie vielleicht heute noch

ein Wechselbalg ohne Adresse.

Ganz egal, ob es um eine Knobelpartie

oder um einen Hurrikan geht,

um fruchtbare Automaten oder um Schußtabellen,

die Kreide in seiner Hand hinkt hinterher –

so schnell ist sein neuronales Netz.

Manisch kritzelt er Hilbert-Räume,

Ringe und Ideale hin. Unbeschränkt

operiert er mit unbeschränkten Operatoren.

Hauptsache: elegante Lösungen,

um den Planeten zum Tanzen zu bringen.

Ein altes Wunderkind mit Schnittstelle zum Geheimdienst.

Wummernd landen die Helikopter auf seinem Rasen.

»Fat Man« auf Nagasaki: reine Mathematik.

Der Krieg als Droge. Eine zu große Waffe

kann es nicht geben. Immer gut gelaunt

beim Lunch mit den Admirälen.

Eigentlich ist er schüchtern, und es gibt Rätsel,

vor denen seine Black Box versagt.

Die Liebe zum Beispiel,

die Dummheit, die Langeweile.

Pessimismus = Sünde gegen die Wissenschaft.

Energie aus der Dose, Klimakontrolle, ewiges Wachstum!

Island in ein tropisches Paradies zu verwandeln –

kein Problem. Der Rest ist nebbich.

Dann der Betriebsausflug auf eine andere Insel,

im Zweireiher, mit geschwärzter Brille: Bikini.

»Operation Wendepunkt.« Der Test war gelungen.

Zehn Jahre brauchte der Strahlenkrebs,

um seine Synapsen abzuschalten.

John von Neumann (1903–1957)

Moon face, double chin, waddling gait:

a stand-up comedian, most likely,

or a salesman for fitted carpets,

a bon vivant from the Rotary Club.

But as soon as he starts to think

watch out for Jáncsi from Budapest!

The soft processor under his skull-cap

will relentlessly tick away,

and with a mere flicker of his memory chip

he will produce a rush of ballistic equations.

In three moves he checkmated Eichmann and Stalin:

Göttingen-Cherbourg, Cherbourg-New York,

New York-Princeton. First Class

he escaped from the Final Solution.

All he needs is four hours’ sleep,

plenty of whipped cream on his Viennese strudel

and a couple of Zürich bank accounts.

Even those who have never heard of him

(and most of us haven’t)

switch with a click of the mouse

into his algebraic circuitry.

Without his own brand of it,

Artificial Intelligence

might never have got off the ground.

Whether it’s a question of playing dice

or detailing a hurricane — you name it..

self-fertilising automata or firing-tables

the piece of chalk in his hand

will lag behind the speed of his mind.

A maniac scribbling down Hilbert spaces,

rings and ideals, operating beyond all limits

with unlimited operators. A few new ideas,

he says, and we could jiggle the planet.

An elderly wunderkind with an interface

to the CIA. Helicopters roaring down on his lawn.

‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki: pure mathematics.

War is his cocaine. There is no such thing

as too big a weapon. Always in high spirits,

lunching with admirals.

A shy fellow at heart. Mysteries

his black box cannot cope with.

Love, for example,

stupidity, boredom.

Pessimism = a sin against science.

Energy out of the can, climate control,

eternal growth! To turn Iceland

into a tropical paradise — no problem!

The rest is nebbich.

Finally: staff outing to another island,

in business suit and blackened glasses,

Bikini. ‘Operation Turning-point’.

The test was successful. The cancer from the radiation

took ten years to turn off his synapses.

Translated by Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Several collections (most of them bi-lingual) of Enzensberger’s poems are available in English:

Hans Magnus Enzensberger: Selected Poems, bi-lingual edition, translated by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Michael Hamburger, Fred Viebahn and Rita Dove, Sheep Meadow Press, Rhineback 1999; Kiosk, bi-lingual edition, translated by Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Michael Hamburger, Sheep Meadow Press, Rhineback 1999; Lighter Than Air, bi-lingual edition, translated by Reinhold Grimm, Sheep Meadow Press, Rhineback 2000; New Selected Poems, bi-lingual edition, translated by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Michael Hamburger and David Constantine, Bloodaxe Books, Hexham 2015

© Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Suhrkamp Verlag, 1957ff.

© Jim Doss and Loch Raven Review, 2008

© Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Bloodaxe Books, 2015

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter