This blog post is part of the German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzie (Lizzies Literary Life) and Caroline (Beauty is a Sleeping Cat). I read Gertrud Kolmar’s poetry in November.

After the end of WWII a heated discussion took place between authors that stayed in Germany during the Nazi era and others who had emigrated.

The controversy was led by two rather mediocre authors, Frank Thiess and Walter von Molo on the side of those who decided to stay in Germany and by Thomas Mann on the side of the literary emigrants. This controversy has left traces until today and the work of W.G. Sebald for example can be only understood when you consider this historical backdrop.

What was it all about?

Thiess and von Molo considered themselves and those authors who were against the Nazis but stayed in Germany as representatives of the Innere Emigration (inner emigration). According to them they suffered consciously the horrors of the Nazi regime to bear witness and to – if possible – send hidden messages to their readers which they smuggled into their books (one reason for the particular popularity of historical novels during this time). While according to them they suffered terror, war and permanent personal threats under the Nazis, the literary emigrants like Thomas Mann or Lion Feuchtwanger lived according to their perception rather well and undisturbed in their comfortable exile and were now, after WWII trying to lecture the “inner emigrants” about moral and declaring the literature of this group of authors per se as worthless.

Thomas Mann who was directly attacked in a rather distasteful way was answering that all books published in Nazi Germany stank of blood and shame and should be destroyed.

Six decades after the end of WWII we can see this controversy in a more rational and distanced, less emotional way. I would say both sides had a point, and both were partly wrong in their judgement.

Indeed, the situation of writers and intellectuals who remained in Germany after 1933 and who were not joining the ranks of the Nazis was very difficult to say the least. Many of them were banned, some were imprisoned and there was a permanent threat on their lives which must have been a terrible strain on them. Some of them complied with the requests of the new regime, some made compromises and only a very few of them really resisted the Nazis completely. Some were discredited in the eyes of the Nazis by their political or racial background – those were the ones that were threatened most, but who anyway rarely had a chance to publish anything during that period. Therefore the term inner emigration is a quite mixed box which contains an assortment of cowards as well as real heroes and all shades in between. But to think that writers who had emigrated had it nice in their exiles is far from the truth that it is insulting and it shows simply the ignorance or mischievousness of the ilk of Thiess and von Molo. Most emigrants were destitute and permanently threatened by expulsion or by the secret agents of the Nazi and Stalinist regime that ruthlessly eliminated critical voices also abroad. The other problem that emigrant authors faced was the lack of publication opportunities and therefore lack of possibilities to make a living. Only Thomas Mann, Feuchtwanger or Stefan Zweig could live from their writing, all the others lived usually miserable from charities.

Also Thomas Mann’s verdict is rather harsh and with all due respect to this great author a bit exaggerated in my opinion. All literature published in Germany between 1933 and 1945 may be morally discredited by the fact that writing and publishing about things that didn’t offend the Nazis included silence about their unbelievable crimes and thus a silent acceptance if not endorsement – still I think that it should be scrutinized on a case to case basis since I am not a supporter of the collective guilt thesis even for books – the question of the literary value is something else. To give an example from the French literature: Celine was an insane anti-Semite who published appalling brochures in which he advocated the mass murder of millions of Jews – but at the same time he is the author of one of the literary most important French novels of the 20th century. Disturbing and disconcerting, but you see the problem here. Sometimes a book is so much better than its author.

There is quite a number of books that were published in Germany during the Nazi era by authors that were no Nazis and that are worth being read today. Some of these books are of high literary value. I want to just drop a few names and titles for those who are interested in finding out more about this interesting topic.

Eugen Gottlob Winkler (1912-1936), the author of excellent essays and an accomplished poet, committed suicide at the age of 24 in order to avoid torture and imprisonment by the Nazis. Unfortunately his slender oeuvre is untranslated in English.

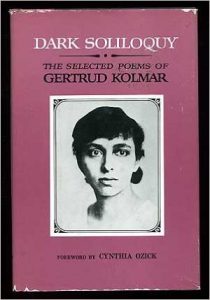

Gertrud Kolmar (1894-1943), one of the most remarkable German poets of the 20th century could publish two collections of poetry in that period although she was Jewish. She was gassed in Auschwitz 1943 or died during the transport from Theresienstadt to the concentration camp.

Jochen Klepper (1903-1942), author of the novel Der Vater (The Father) and of posthumously published diaries committed suicide with his Jewish wife and stepdaughter after their emigration request was denied.

Albrecht Haushofer (1903-1945), fellow student of Rudolf Hess and son of NS geo-politician Karl Haushofer, but nevertheless a member of resistance circles wrote his Moabiter Sonette (Moabit sonetts) while in prison; the manuscript was found in his coat pocket after he was executed by an SS commando a few days before the end of the war in Berlin.

Felix Hartlaub (1913-1945), whose diaries are of highest literary and documentary value disappeared without traces during the final battle of Berlin in the first days of May 1945.

Friedo Lampe (1899-1945) published a novel that was immediately banned after publication, and another one that was censored by the Nazis. Lampe, who was probably the stylistically most advanced writer of his generation, was shot a few days after the end of WWII by a Russian soldier.

Most of these authors were never translated into English, which is a pity. Only Haushofer and Kolmar are so far known to the English-reading public.

Here is an example of Gertrud Kolmar’s (i.e. Gertrud Chodziesner) poetry:

Der Engel im Walde

Gib mir deine Hand, die liebe Hand, und komm mit mir;

Denn wir wollen hinweggehen von den Menschen ….

So lass uns fliehn

Zu den sinnenden Feldem, die freundlich mit Blumen und Gras unsere wandemden Füsse trösten,

An den Strom, der auf seinem Rücken geduldig wuchtende Bürden, schwere,

giiterstrotzende Schiffe trägt,

Zu den Tieren des Waldes, die nicht übelreden …

Wir werden dürsten und hungem, zusammen erdulden,

Zusammen einst an staubigem Wegesrande sinken und weinen…

The Angel in the Forest

Give me your hand, beloved, and follow me.

And we will go away from men. . . .

So let us flee

Unto the musing fields that will console our wandering feet with friendly flowers and grass,

Unto the river, bearing patiently upon its back the weighty burden of the full,

freight-laden ships,

Unto the forest animals that speak no ill ….

And we will thirst and hunger and endure together,

And together someday on a dusty roadside we will fall and weep …

(translation by Henry A. Smith)

Kolmar had the opportunity to emigrate but refused. She didn’t want to leave her old father unattended back in Germany. The exact date of her death is unknown. Since there is a record of her on the transport lists from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz from 2 March 1943 but no record in the lists of inmates in the concentration camp it means that she was most probably gassed immediately after her arrival there or died during the transport.

Reading her poetry (or works of any other victim of that regime) one should remember well her verses from the poem Die Dichterin (The Woman Poet):

Mein Herz wie eines kleinen Vogels schlägt

In deiner Faust. Der du dies liest, gib acht;

Denn sieh, du blätterst einen Menschen um.

Doch ist er dir aus Pappe nur gemacht.

My heart beats like that of a little bird

In your fist. You who read this, take care;

For see, you turn the page of a person.

Though for you it is only made of cardboard.

(translation by Henry A. Smith)

For those interested in Gertrud Kolmar’s poetry and life, I can highly recommend the biography by Dieter Kühn: Gertrud Kolmar. A Literary Life. Kolmar, like all the other authors I mentioned, is worth to be discovered.

Gertrud Kolmar: Das lyrische Werk, Kösel, München 1960

Gertrud Kolmar: Dark Soliloquy, transl. Henry A. Smith, Seabury Press, New York 1975

Gertrud Kolmar: A Jewish Mother from Berlin – Susanna, transl. Brigitte M. Goldstein, Holmes & Meier 2012

Gertrud Kolmar: My Gaze Is Turned Inward: Letters 1938-1943, transl. Johanna Woltmann, Northwestern University Press 2004

Gertrud Kolmar: Worlds – Welten, transl. Philip Kuhn and Ruth von Zimmermann, Shearsman Books 2012

Dieter Kühn: Gertrud Kolmar. A Literary Life, transl. Linda Marianiello, Northwestern University Press 2013

Eugen Gottlob Winkler: Dichtungen, Gestalten und Probleme. Nachlass, Neske, Pfullingen 1956

Jochen Klepper: Der Vater, dtv, München 1991

Jochen Klepper: Unter dem Schatten deiner Flügel. Aus den Tagebüchern der Jahre 1932-1942, Brunnen, Gießen 2005

Albrecht Haushofer: Moabit Sonnets, transl. M.D. Herter Norton, W.W. Norton, New York 2013

Felix Hartlaub: In den eigenen Umriss gebannt (2 vol.), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2002

Felix Hartlaub: Kriegsaufzeichnungen aus Paris, Suhrkamp, Berlin 2011

Felix Hartlaub: Italienische Reise, Suhrkamp, Berlin 2013

Friedo Lampe: Septembergewitter, Wallstein, Göttingen 2001

Friedo Lampe: Von Tür zu Tür, Wallstein, Göttingen 2002

Friedo Lampe: Am Rande der Nacht, Wallstein, Göttingen 2003

Friedo-Lampe-Gesellschaft e.V.: Ein Autor wird wiederentdeckt: Friedo Lampe 1899-1945, Wallstein, Göttingen 1999

Johannes Graf: Friedo Lampe (1899-1945). Die letzten Lebensjahre in Grünheide, Berlin und Kleinmachnow, Frankfurter Buntbücher, Frankfurt/Oder 1998

Patrick Modiano: Dora Bruder, transl. Joanna Kilmartin, University of California Press, Oakland 2014 – Modiano mentions Friedo Lampe and Felix Hartlaub in his novel.

© Kösel Verlag, 1960

© Henry A. Smith and Seabury Press, 1975

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter