This review is part of the German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzie (Lizzies Literary Life) and Caroline (Beauty is a Sleeping Cat)

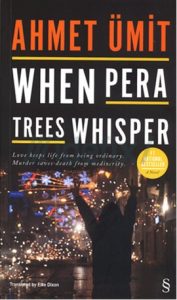

Kemal Kayankaya – the name is without doubt Turkish. But Kemal doesn’t speak Turkish because he was adopted by a German couple when he was still a toddler. His parents, immigrants from Anatolia in Frankfurt/Main, died young. And so Kemal grew up like any other German child, except for his name.

A very clever choice by the author, I can say. Because it makes the hero of Happy Birthday, Turk! a born outsider – for many Germans he is the Turk who they think cannot speak proper German and should probably work as a garbage collector and for the Turks he is encountering in his work as a private investigator he is the fellow countryman who truly understands them because he has the same background as they do. But both sides are wrong.

In reality this cocky, quick-witted young man in his late twenties with the talent for seeking trouble who after several attempts to find his true vocation somehow acquired a license for his business, and who has an issue with alcohol, is – like many literary heroes of this genre – a romantic to the core. Just scratch a bit on the surface and you will see…

And this is the case with which the Philip Marlowe of Frankfurt has to deal in this book:

Ahmed Hamul, the husband of Ilter, Kayankaya’s client, was found stabbed to death on the streets of Frankfurt’s red light district. Since the police is not very eager to solve the case and because the wife has little trust in them, she is asking her alleged compatriot for help to find out who murdered her husband. Kayankaya accepts and finds himself soon in a case that gets much bigger than he initially thought.

While meeting the family, K. remarks that the brother-in-law has a particularly low opinion of the victim and except for Ahmet’s widow nobody seems really very interested in finding the truth. Also that the family is hiding the youngest daughter under the pretext that she is ill is a hint for the private eye that something is fishy here.

The police proves little willingness to give the needed information to Kemal and his impudent behavior to some of the admittedly racist policemen doesn’t exactly help. Kommissar Futt (a dialect word for vagina by the way), one of the least endearing exemplars in this biotop is leading the investigation and makes it a personal issue to keep Kayankaya, who fooled him once as alleged investigator from the Turkish Embassy, in the dark.

But fortunately, Kayankaya is in friendly terms with the retired police commissioner Löff who is pulling some strings with his former colleagues and is also later of great help. The slightly chaotic Kayankaya and his unofficial assistant who in his very German pedantic way tries to teach his friend some order and discipline and organization are an odd couple and this adds to the humor in the book which is frequently supported by witty dialogues and descriptions.

While some facts are hinting at a conflict in the red light district – Ahmet had obviously a girl friend among the prostitutes there – it is soon obvious that the issue is bigger than Kayankaya thought. It turns out that Ahmet was close with his father-in-law, who got killed in a car accident just months before. Unless the car accident wasn’t exactly an accident as one of the children that witnessed the event, claimed. But Kayankaya cannot ask the child, because it too fell victim to an accident…

I don’t want to give the whole story away, that would spoil the fun for possible future readers of the book. Honestly speaking, the plot was rather conventional and I saw it more or less coming from an early stage of the book.

But when this sounds a bit derogative, I don’t really mean it. Arjouni was 23 when the book was published first and it is quite an accomplishment for such a young author to deliver such a fast-paced classical hard-boiled crime novel with an interesting main character.

And there is more to the book. As someone who has lived in Frankfurt for several years in the 1990s I can say that the book gives an authentic impression of the place to its readers. Starting from the Frankfurt dialect that is used in the German version (yes, Kayankaya “babbelt” frequently in Frankfurterish – how funny is that?) to the description of the locations (“Wasserhäuschen” inclusive – a kind of kiosk open 24/7, literally “little water house”, the typical place for an alcoholic to buy and drink his booze), it all fits. And there are plenty of hilarious situations that give Kayankaya not only opportunity for acerbic or ironic remarks but also for a playful inventiveness on his (and the author’s) side.

Was Frankfurt, the city with the highest percentage of migrants (and the highest crime rate in Germany) really that racist in the 1980s? I cannot really say from my own experience – but I am not a migrant and my living conditions and the milieu in which I lived and worked there a few years later were very different from Kayankaya’s. Since the whole book is so well written and researched, probably it was.

A good decision by the author was also to choose Frankfurt and not Berlin as the location for this novel. In no other place in Germany is the connection between big money and crime so tangible as here, no other city in Germany looks like a miniature version of Metropolis, no other city has this mixture of backwater mentality and delusions of grandeur.

The only bad thing about the book is that it is such a fast read. I finished it in one sitting during a flight from Istanbul to Almaty. But there are four more Kayankaya novels and I am quite sure you will like all of them. (The whole set is translated and available in the Melville International Crime series)

Jakob Arjouni died last year after a long battle with cancer. A real loss for German literature and especially for crime fiction aficionados. I can also strongly recommend his Magic Hoffmann, a crime novel too (but without Kayankaya).

Jakob Arjouni: Happy Birthday, Turk!, transl. by Anselm Hollo, Melville House, New York 2011

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter