“The desert is a true treasure

for him who seeks refuge

from men and the evil of men.

In it is contentment,

In it is death and all you seek.”

This muwwal, a traditional song, performed by the Sufis in the community at Uwaynat is quoted by Asouf’s father in Ibrahim al-Koni’s novel “The Bleeding of the Stone”. And this muwwal seems indeed to express perfectly what the desert means to the hero’s father.

Asouf grows up somewhere in the Libyan desert, living the traditional life of Bedouins who are the only inhabitants of this great landscape that seems so hostile to any outsiders and that is therefore the perfect place for people like Asouf’s father, a loner. When some other bedu families move to their valley, he forces his own family to move to an even more remote place simply because he can’t stand the vicinity of other people, much to the regret of Asouf’s mother who seems to be considerably more sociable and probably also to Asouf himself, who never had other children to play with and who is of an age where his interest in girls is growing. But the Tamba sandals that Asouf is receiving as a present and that are

“embellished by the nimble fingers of the girls of Tamanrasset, who poured into the designs their passion and their longing to meet the knight of their dreams”-

that’s as close as he ever comes to a girl.

Asouf is taught by his father how to survive in the desert, how to hunt, how to always treat his camel with respect and even tenderness, and how to spare water and bullets.

“In the desert, he’d go on, water and bullets were like air, the very foundation of life. If you ran out of the first, you’d die of thirst, and if you ran out of the second, some enemy, man or beast or snake, would strike you down. Water and bullets were the life blood of a lone man.”

Hunting is not a sport in this traditional society – it is simply necessary to survive. To kill more animals than necessary, or to kill a pregnant animal, is therefore out of the question. Asouf’s father, as a true Sufi, admires the beauty of the gazelle and he is suffering from the fact that he sometimes has to kill one of these creatures because it is necessary for the survival of his family.

Also with the waddan, a kind of desert moufflon, he has a special mystical relationship and one of the worst moments of his life is the moment when he has to kill a waddan because his family is starving and the meat of the waddan the only available food. The waddan is also instrumental in the death of Asouf’s father who would see in this outcome probably the deserved fate of someone who broke his oath to never hunt and kill a waddan.

Asouf is at the time of his father’s death already a young man who knows the secrets of the desert. He is tending his goats and knows the places where the rare waddan, already extinct in most other regions where it used to live, is hiding. Asouf has become a vegetarian, a true son of his Sufi father. But his quiet pastoral lifestyle is threatened: “civilization” and its agents are slowly trickling into Southern Libya (the Italian war against Abyssinia is mentioned, so the story is taking place in the 1930s as it seems). Government officials arrive and declare Asouf to be from now on the custodian of the prehistoric rock paintings that have started to raise some interest from the side of archaeologists and other scientists; small tourist groups from abroad start to visit the place. Asouf sees these visitors and their (to him) very strange behavior with some interest but he keeps a careful distance, partly because of his great shyness. He hides his blushing and embarrassment behind his veil, one of the typical adornments of the male dress in the traditional Tuareg culture. The government employees are surprised that Asouf is rejecting their salary – but for Asouf, money is worthless because everything he needs he can find in the desert.

These mild “clashes of civilizations” are unfortunately only the harbinger of worse things to come: one day two hunters with a big hunger for meat – they take pride in having killed the last gazelles in the north just for the fun of it – are arriving with their jeep and ask from Asouf to help them to find and hunt the waddan…the reader can already imagine how this encounter between a traditional culture and a “modern” civilization will end – with the victory of the party that has the bigger firepower and no moral qualms on its side, i.e. with the victory of the “modern” and “more advanced” party.

The desert is the setting of most of the works of Ibrahim al-Koni, and it is of course also a metaphor for (among other things) the human power to resist. This novel also raises ecological questions, questions related to the lessons we can learn from traditional societies in terms of how to lead a sustainable life that is not based on the short-sighted over-exploitation of natural resources. It is a book that breathes the air of the desert and the deep respect the people living traditionally in this habitat feel for everything that lives and even for the stones and sand that is surrounding them.

Ibrahim al-Koni was born 1948 in Southern Libya and grew up in a traditional Tuareg family. He started to learn Arabic at the age of 12 and studied later literature at the Maxim Gorki Institute in Moscow. After having worked as a journalist in Russia and Poland, he is living since many years in Switzerland.

For those who don’t know his work, “The Bleeding of a Stone” is an excellent opportunity to discover this extraordinary author. It’s a wonderful book.

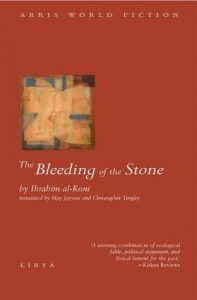

Ibrahim al-Koni: The Bleeding of the Stone, transl. by May Jayyusi and Christopher Tingley, Interlink Books, New York Northampton 2002

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter