This review is part of the German Literature Month, hosted by Lizzie (Lizzies Literary Life) and Caroline (Beauty is a Sleeping Cat)

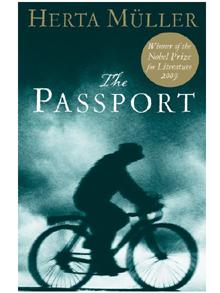

When in 2009 the Nobel Prize Committee awarded the Prize for Literature to Herta Müller, whose opus magnum The Hunger Angel had just appeared in print, I thought that at least this one time the jurors in Stockholm had shown not only that they are able of a decent choice, but that sometimes they have even a sense of timing. Because The Hunger Angel marked the point when Herta Müller got also outside the German-speaking world the attention she deserves. Her first translated work available in English, The Passport, got some favorable reviews but was commercially not a big success.

Müller’s works – and The Passport is no exception – are almost exclusively set in Romania, the country in which she was born and grew up in a small German village (Nitzschkydorf) during the time of the more and more paranoid dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu. Although Romania didn’t adopt a policy of ethnic cleansing after WWII against the ethnic Germans living there since centuries like most other Eastern European countries did, the situation for the Banat Swabians (Donauschwaben) and the Saxons in Transsylvania (Siebenbürger Sachsen) was far from comfortable.

Most of them had embraced the Nazi ideology during the war, many enrolled in the SS, and the whole community had to pay a high price after the war for this act of treason as it was seen: a big part of the men and women from the German community were sent as slave workers to Siberia for five years and more. Many of them died there and those who survived came back considerably aged and without any hope or illusion for the future. In Siberia they had seen what they before refused to see: that people are able to do any act of cruelty or moral sordidness for a piece of bread.

This is the historical backdrop of The Passport, a very short book of only 100 pages, with chapters that are short or even very short. But this book is anything but a fast and easy read.

Windisch, the village miller, has decided to apply for a passport for himself and his family. The passport is necessary if you want to travel abroad or emigrate to (Western) Germany, as the Windischs plan. Windisch is already waiting more than two years and a half, but doesn’t seem to make any progress with his application, despite the fact that he is bribing the mayor with sacks full of flour. But the flour is not enough, the priest (he has to issue the birth certificates) and the militiaman (his support is crucial for receiving the passports) also need to be bribed.

When Windisch finally understands what these two men want, he is sending his daughter to them…After she sleeps with them, the passport will be finally arranged. In the last chapter we see the Windisch family coming for a visit to their home village after their emigration. While many other Germans emigrated too, a few, like Konrad the night watchman have not. Konrad has even married and intends to stay in Romania, despite all the problems.

Müller arranges her material in a very interesting way. The short chapters have sometimes the character of stand-alone short stories, sometimes they are like vignettes that allow the reader for a moment to catch a glimpse of something that he usually would not see.

One of the most remarkable things in Müller’s book is the language. Very simple and short compact sentences full of poetic, sometimes surrealistic metaphors. The German title would be literally translated “A man is nothing but a pheasant in the world”, obviously a local saying that is quoted in an early conversation between Windisch and Konrad by the latter. Windisch retorts that a man is strong, stronger as the beasts, but later after his daughter Amalie has slept with the village officials, he is repeating Konrad’s sentence as if to remind the reader that he was wrong and too optimistic about the strength of man.

The story of Windisch and his family is intervowen with other stories: the story of Rudi the glass maker who is not right in his head, and his parents; the story of Dieter, Amalie’s friend, who is shot dead while obviously attempting to cross the Danube to Yugoslavia; the story of Konrad, the night watchman; the story of the skinner and his wife; the story of the carpenter; and also stories that are told like anecdotes from the past: the story when the king passed by with his train before the war and the village couldn’t sing the welcome song because the king was asleep and his entourage insisted on not waking him up for some villagers; and there are even stories about the owl that was seen in the village and that the villagers consider as a sign for something to happen; and most disturbingly the story of the apple tree that was eating his own apples before the war and that had to be burned therefore to drive away all the evil.

There are signs of alienation everywhere. When Windisch passes the church, he wants to go inside to pray. But:

“The church door is locked. Saint Anthony is on the other side of the wall. He is carrying a white lily and a brown book. He is locked in.”

There is no hope to be expected in this world from the church, St. Anthony, or even God. Later in the book, when we learn about the disgusting priest, who uses his power position – without birth certificate no emigration – to extort sex from the women he fancies, we understand why.

There is alienation of course between the Romanians and the Germans; the Romanians are contemptuosly called “Wallachians” by the Germans and vice versa the Romanians wonder how, after Hitler, it is possible that there are still Germans in Romania. But it is not only for the Romanians that the Swabians feel contempt, the same goes for their feelings for the Germans in Western Germany, especially the women. “The worst Swabian woman is still better than the best over there.”

Children cannot escape this paranoid world of the village where the Securitate, the mighty intelligence network of the secret police is watching over everything. Amalie, who works as a schoolteacher, is instructing the kids:

“Amalie points on the map. “This land is our Fatherland”, she says. With her fingertip she searches for the black dots on the map. “These are the towns of the Fatherland,” says Amalie. “The towns are the rooms of the big house, our country. Our fathers and mothers live in houses. They are our parents. Every child has its parents. Just as the father in the house in which we live is our father, so Comrade Nicolae Ceausescu is the father of our country. And just as the mother in the house in which we live is our mother, so Comrade Elena Ceausescu is the mother of our country. Comrade Nicolae Ceausecu is the father of all children. And Comrade Elena Ceausescu is the mother of all children. All the children love comrade Nicolae and comrade Elena, because they are their parents.” ”

(It is rather embarrassing that The Times Literary Supplement (!) claims in its review: “Every such incidence of misdirection is the whole book in miniature, for although Ceausescu is never mentioned, he is central to the story, and cannot be forgotten.” – This happens when reviewers don’t read the book they are supposed to write about.)

Even worse is the alienation between men and women. Men use their position to get what they want from the women: sex. In Siberia, Amalie’s mother was a whore. She was selling her body for food and warm clothes in order to survive, and now Amalie is stepping in her mother’s shoes, spreading her legs for the priest and the militaman to get herself and her family out of this place where all the children love the parents of the country so much.

It is revealing that when she was a child and was almost raped by Rudi, her father was blaming her, not Rudi: “Amalie will bring disgrace down on us.” The conversation that the drunk Windisch, his wife and his daughter have over lunch after Amalie’s visit to the priest and the militiaman, is rather depressing, but it shows exactly how things are between men and women in this village, in this society:

“Windisch’s wife sucks the small, white bones. She swallows the short pieces of meat on the chicken’s neck. “Keep your eyes open, when you get married,” she says. “Drinking is a bad illness.” Amalie licks her red fingertips. “And unhealthy,” she says. Windisch looks at the dark spider. “Whoring is healthier,” he says. Windisch’s wife strikes the table with her hand.”

The Passport is a difficult, sometimes even depressing read. A paranoid system like Romania under Ceausescu is doing the things to people that Herta Müller is describing in this book. It is poisoning even the most private feelings, activities, relationships. It is easy to understand that the author’s honest, unvarnished description of German village life in the Banat didn’t bring her many friends in her own community. Until recently she was still the target of smear campaigns of former Securitate agents and Danube Swabians who want to paint a nicer picture of their own past – for whatever reasons.

If you look for an easy, fast, superficially enjoyable book – this one is not for you. But if you like to read a beautifully crafted, multi-layered book about the human condition in times like ours, I can heartily recommend The Passport to you. It is also a reminder that there is absolutely nothing to feel nostalgic about for any dictatorship like Ceausescu’s Romania was.

Herta Müller: The Passport, transl. by Martin Chalmers, Serpent’s Tail, London 1989

Other Reviews:

Winstonsdad’s Blog

Book Around The Corner

The Reading Life

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter