As mentioned some time ago, I am an unsystematic collector of anecdotes that have writers as subject. Here are two of them about one of the giants of German 20th century literature, Robert Musil.

Musil worked for decades on his unfinished masterpiece Man without Qualities and published comparatively little during his lifetime. As a result of his obsessive efforts, Musil was always living in very precarious financial conditions and during his exile in Switzerland during the last years of his life, he was really destitute.

Musil seemed to have been a proud, extremely self-assured, maybe even arrogant person who had a very high opinion regarding his own abilities as a writer and he detested writers that were (contrary to him) popular and successful. With particular disdain he looked at the output of Stefan Zweig and Thomas Mann. While he couldn’t deny that Thomas Mann had talent – and success! – and he probably hated him just because of that, Stefan Zweig was another case. Zweig was according to Musil shallow, superficial, trivial, always responding to the requirements of the market that liked to read another collection of (in Musil’s opinion) not very accomplished novellas or another biography in Reader’s Digest style, Zweig’s slickness and wish to fit in, to be the centre of the attention of a circle of rich people and of the literary establishment, always very much concerned about increasing his bank account, his collection of antiquities and old manuscripts. In short: Stefan Zweig was for Musil the personification of everything that was wrong with the literature of his time.

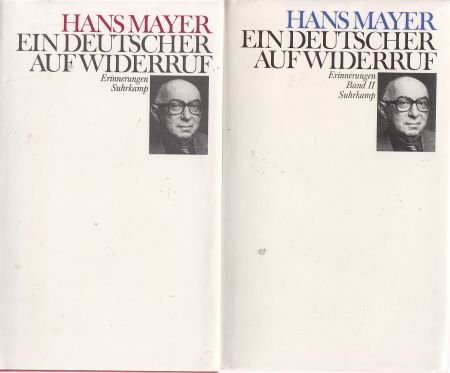

Hans Mayer, the great German-Jewish literary critic, writes in his autobiography Ein Deutscher auf Widerruf how he visited Musil at his home in Switzerland during their emigration. It was 1940, and there was a widespread fear that the Nazis might invade also Switzerland.

“Musil couldn’t get into the USA, and Mayer was suggesting the relative obtainability of Colombian visas as a pis aller. Musil, he wrote, ‘looked at me askance and said: Stefan Zweig’s in South America. It wasn’t a bon mot. The great ironist wasn’t a witty conversationalist. He meant it … If Zweig was living in South America somewhere, that took care of the continent for Musil.’” (quoted by Michael Hofmann: Vermicular Dither, London Review of Books, 28. January 2010)

In the third volume of his autobiography, Elias Canetti describes how he after completion of the manuscript of Die Blendung (Auto-da-fe) in 1931 sent it as a parcel with an accompanying letter to Thomas Mann, hoping that Mann would read it (and possibly recommend it to a publisher). Alas, the parcel came back unopened with a polite letter by Mann, telling the unpublished author that he was not able to read the book due to his work schedule (Mann was working on his multi-volume Joseph novel at that time). The disappointed Canetti put the manuscript aside for a long time, until Hermann Broch arranged a few readings for him in Vienna. One of them was also attended by Musil who allegedly said to Broch: “He reads better than myself.” (Not surprisingly, Canetti was an extremely gifted stage performer in the mould of Karl Kraus.)

Later on, when the novel was finally published in 1935, Canetti wrote again to Mann, who now – four years later! – congratulated Canetti and wrote also very positively about the novel (which in all probability he hadn’t read except for a few pages). With this letter in his pocket and beaming with self-confidence Canetti was running into Musil one day when Musil brought it about himself to also congratulate Canetti. Not knowing about Musil’s strong antipathy regarding Thomas Mann, Canetti blurted out: “Thank you, also Thomas Mann praises my book!” – to which Musil answered with a short “So…”, turning around and ignoring Canetti for the rest of his life.

In defence of Zweig and Mann it has to be added that both writers supported many of their colleagues in need particularly during their time of emigration. Musil was during his last years ironically mainly living from a grant he received from an organisation that supported writers in need and that was mainly funded by – Thomas Mann. Musil knew about that and felt probably terribly humiliated.

Hans Mayer: Ein Deutscher auf Widerruf, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982/84 (2 vol.) – there is unfortunately no English translation of this highly interesting autobiography.

Elias Canetti: The Play of the Eyes (Das Augenspiel), translated by Ralph Manheim, Farrar Straus Giroux 2006

Michael Hofmann: Vermicular Dither, London Review of Books, Vol. 32, No. 02, p. 9-12, 28 January 2010 – Hofmann’s article is a real assassination of Zweig; very, very harsh and spiteful indeed, but nevertheless worth reading because he points at various serious flaws in Zweig’s writing.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter