Alfred Döblin has left a huge literary oeuvre: novels, stories, essays, autobiographical and literary theoretical writings, and more. His importance as a writer has been emphasized by many of his contemporaries (Brecht, Benn, Tucholsky, Feuchtwanger to name a few) and some authors of the post-war generation. His work is available in German in several editions, including two paperback editions. In 1979, Günter Grass donated the Alfred Döblin Prize, which has become one of the most important literary prizes for German-language literature, and in 1984 the International Alfred Döblin Society was founded, which is intensively involved in the exploration of Döblin’s work.

Nevertheless, Döblin is not a very popular author in the German-speaking countries. The mostly read work is undoubtedly Berlin Alexanderplatz, a book that is frequently compared with Ulysses or Manhattan Transfer in terms of its literary importance. Despite this fact, it is a book that is not easy to digest, and it is hardly suitable for a cozy reading in bed. The impression this book left on many readers may have prevented them from discovering other translated works of this author. This lack of interest also applies to Döblin’s reception outside the German-speaking countries; only a fraction of his work is available in translations and here, too, at most Berlin Alexanderplatz receives some attention. (Translated works available in English are: The Three Leaps of Wang Lun, November 1918, Tales of a Long Night, Men without Mercy, Journey to Poland, or Destiny’s Journey; Manas and Mountains Oceans Giants will be released in English translation in 2020 by Galileo Publishers.)

In his text On My Teacher Döblin Günter Grass addressed in 1967 some of the reasons why Döblin could not really catch up with the German reading public after the Second World War:

“Döblin was not trendy. He was not popular. He was too catholic to the progressive left, too anarchic to the Catholics, he denied solid theories to the moralists, he was too inelegant for the night program, he was too vulgar for the school radio; neither the ‘Wallenstein‘ nor the ‘Giant‘ novel could be digested easily; and the emigrant Döblin dared to return home in 1945 to a Germany that would soon devote itself to consumerism. As for the market value: the asset Döblin was and is not listed on the literary commodity market.” (Translation T.H.)

And for many, one might add, this converted Jew, who returned from exile to Germany wearing a uniform of the French occupiers, was simply suspect – one who didn’t belong here and whose presence was rather embarrassing, for reasons that have also to do with a deep-rooted anti-Semitism that didn’t disappear just like that after 1945 but that only went into hiding for a while.

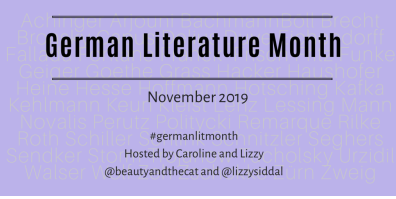

This year, Berlin Alexanderplatz is the subject of a readalong in the context of German Literature Month and I hope that this will increase the interest in Döblin. Personally, I have decided to discuss another work, which seems to be rather marginal, but which nevertheless makes it possible to contribute to the better understanding of this author. I am talking about the book “My address is Sarreguemines” (“Meine Adresse ist: Saargemünd“), a work that explores Döblin’s significant relationship with the French-German border region near the Saar, with Lorraine and the Saarland. (The book is available in German, as well as in a French translation.)

Döblin, who had a doctor’s practice in Berlin, volunteered for military service in 1915 and was assigned to Sarreguemines. The French town of Sarreguemines is now located directly on the German-French border, but between 1871 and 1918 Lorraine was part of the German Reich (it had been annexed after the victory in the Franco-German War in 1870/71). The volume “My address is: Sarreguemines”, which collects various texts that illuminate Döblin’s relationship to the German-French border region, begins with letters from this period (1915-1918), which he sent from Sarreguemines and later from Hagenau in Alsace (he had been transferred there briefly before the war after a conflict with a superior over the provision of food to the patients.)

It is interesting to see how Döblin’s attitude regarding the war changed over time. While he hailed in an early letter – although already ironically broken – a victory at the eastern Front, he becomes more and more disillusioned and skeptical about the war and its futility as the slaughtering is dragging on for years. Privately he may have spoken even more openly but due to the existing censorship Döblin was not elaborating on this topic in his letters from that period.

Most important for the reader, who is interested in Döblin’s literary work, are in the period between 1915 and 1918 his letters to Herwarth Walden. The journalist Walden – he was first married to Else Lasker-Schüler – was a close friend of Döblin since their youth. At the same time Walden was the publisher of the magazine Sturm, which became the preferred publication platform of many expressionist and modernist authors. In addition, Walden operated the Sturm Gallery and under difficult conditions made a contribution to the popularization of many expressionist artists that can hardly be underestimated. (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example, exhibited at the Sturm Gallery, illustrated the first book by Döblin and later also painted his portrait).

Döblin, at the time a published (two volumes with stories and numerous contributions in magazines), but moderately successful author, used the Sturm during this time as the most important organ for the publication of his stories. With Walden he talks about book projects – his first novel The Three Leaps of Wang Lun and another book with stories are being published during this period, two more novels are almost completed or in preparation – but also occasionally on reading experiences that are often disappointing (e.g. he expresses complete disappointment over a novel by Heinrich Mann). In his letters to Walden, Döblin also describes his difficulties with his literary work in Sarreguemines. This is partly due to his work as a doctor – Verdun is about 100 km away, and the cannon thunder from there can be heard in Sarreguemines. For the work on a historical novel (Wallenstein will be published after WWI), that requires access to secondary literature, Sarreguemines is not a good location; only rarely can he get some of the books he needs urgently from the library in Strasbourg.

In addition, Döblin has financial worries (which get better later); he suffers from cramped living conditions, narrow-minded colleagues and superiors and his health is not always the best. Although he is vaccinated, he is contracting typhus and has severe necrosis, which necessitates several stays in German spas. As if that were not enough, Döblin also has a fling with one of the female doctors at the hospital; the young lady is being transferred to Berlin shortly before the arrival of Döblin’s family. (Walden, to whom Döblin confides these details, receives the Berlin address of the lady from his friend, with the cryptic remark that this may come in handy for him one day…)

Döblin’s feeling regarding the arrival of his wife and children who will live with him, are ambiguous. He is happy to have his growing family around him (his wife will bring their two sons to Sarreguemines, a third son will be born there, a fourth son in the post-war years; Döblin also has a son from an extramarital relationship whom he secretly supports financially). On the other hand, the noise at home, the frequent quarrels with his wife are obstacles that lead to a slowdown of his literary production. (Döblin’s marriage to his wife Erna, a trained physician, was extremely turbulent, but it lasted until his death. Döblin’s propensity to marital infidelity may have been one of the reasons for the frequent quarrels of husband and wife.) The situation only improves after the family moves to a slightly bigger flat in which Döblin is “smartly” (as he writes to Walden) arranging a spatial separation: while he is living upstairs, wife and children stay downstairs and don’t disturb him when he is working or needs a rest.

A little peace and relaxation Döblin finds during this time on occasional visits to Saarbrücken. By far the largest city in the region, it offers the urban life, a more open, cultured atmosphere compared to the Lorraine garrison town of Sarreguemines that he misses so much. However, the confrontation with his superior also takes place in Saarbrücken, which ultimately leads to his punitive transfer to Haguenau. (This event happens coincidentally at exactly the spot where the hospital in which I was born is located.)

After the end of the war and demobilization Döblin returns to Berlin (he later used these experiences in the first of his four-volume work November 1918). The twenties and early thirties are the time of Döblin’s greatest productivity and success as an author; he and his family can for the first time live without financial worries, if only for a few years.

Döblin didn’t burn the bridges to the Saar region, which was from 1920 to 1935 not a part of Germany but under International Administration by the League of Nations. He corresponds with the essayist Arthur Friedrich Binz from Saarbrücken who is publishing in 1924 an essay Alfred Döblin und das Saarland (Alfred Döblin and the Saarland); Binz mentions also that two of Döblin’s wartime stories are playing in the German-French border area: Der Geist vom Ritthof (The Ghost of the Ritthof) und Das verwerfliche Schwein (The reprehensible Pig), two grotesque ghost or horror stories still written in the spirit of Expressionism. (The essay of Binz is reprinted as well as the two stories by Döblin in the book.) Döblin also wrote at least two more texts, which were then published in Saarland media. And he campaigned for the publication of the first novel by Anton Betzner, an author that lived at the Saar region for many years; the then still very young author proved later to be a very important supporter of Döblin after WWII.

A drastic deterioration in living and publishing conditions began for Döblin in 1933. As a Jew and leftist, he had to flee; in France he worked for some time – together with the scholar Robert Minder, a professor for German literature – in the Ministry of Information (Minister: Jean Giraudoux). After the invasion Döblin had to flee again under adventurous circumstances. Via Portugal he finally arrived in the USA, where he was initially working as a scriptwriter at MGM; later, he and his family lived on the financial support of various aid organizations. Döblin’s conversion to Catholicism also falls into the period of his American exile.

In 1945 Döblin returned to Germany via France; he entered his country of birth as a French citizen and in the uniform of a French Colonel. Firstly in Baden-Baden and later in Mainz, he worked for the French Military Administration on the reconstruction of literary institutions; he also founded the literary magazine Das goldene Tor (The Golden Gate), which was to play an active role in the democratic transformation of Germans; it became a platform for new talents and authors that had remained in Nazi-Germany but had kept a distance to the regime; also exiled authors were published. Döblin was supported in this task by Anton Betzner, whom he could win as editor for the magazine. In addition, Döblin completed various of his own works. Radio broadcasting became an important publication channel for him. The letters to Betzner from the years 1946-1953 that are included in the reviewed volume reflect the editorial work in the magazine Das goldene Tor. But the letters show also an increasing disappointment of Döblin: despite Betzner’s efforts and publishing contacts Döblin can not secure a publishing contract for his Hamlet novel for many years; and he despairs more and more with the restorative tendencies in the post-WWII West Germany. (Betzner proves in the decades to come one of the few who on many occasions promoted Döblin’s literary oeuvre by essays and radio features.) Only occasionally Döblin’s sharp wit seems to be revived. But these last years are also a period of various health ailments for Döblin – he has an infarct and is struggling with progressive Parkinson’s disease. After West German President Theodor Heuss (himself a writer and author of several essay collections) intervenes in favor of Döblin in the financial compensation proceedings, the author finally receives a settlement, and is able to buy a tiny apartment in Paris. There he lives with his wife – apart from frequent visits of his friend Robert Minder – almost completely isolated from 1953 on. Döblin dies during a spa stay in Emmendingen in 1957, already forgotten by most of his contemporaries. His widow will take her life a few months after his death.

Alfred Döblin and his wife are buried in the small village of Housseras in Lorraine (approximately 500 inhabitants), where his son Wolfgang (Vincent Doblin is the French version of his name), who died in tragic circumstances, is also buried. Döblin, who after his return to Europe found out that several of his closest relatives had been murdered in Auschwitz, had lost contact with his son Wolfgang (Vincent) during the war, who served as a soldier in the French army. Wolfgang, who was a highly gifted mathematician, had some conflicts with his father in his youth, who had always hoped during the time of the separation during the war to reconcile with his son one day. But this reconciliation could no longer take place, Wolfgang had died during the war, as the shocked parents learned in March 1945. Afterwards Alfred Döblin apparently suffered greatly from feelings of guilt. Döblin and his wife decided to be buried later at the side of Wolfgang.

The book reviewed here gives further details about the circumstances of Wolfgang’s death. To avoid imminent capture by German troops, the desperate young man had shot himself on a farm in Housseras. After he had been buried in a mass grave, he was later exhumed and buried in a solitary grave. The house where he died carries today a memorial plate with the note “mathématicien de génie”, and his grave plate mentions that he died for France (“mort port la France”). (Photos and further information can be found also in this interesting French-language article.)

A sealed envelope, which Wolfgang had sent to the French Academy of Sciences, was opened in 2000. The envelope contained a significant unpublished mathematical manuscript on stochastic processes Sur l’équation de Kolmogoroff, which anticipated findings of the Japanese mathematician Itō Kiyoshi. On Wolfgang Doeblin’s life and work there is an interesting book by Marc Petit, which I refer to at the end of the article.

The last text by Alfred Döblin in the volume reviewed here is his speech in Saarbrücken about the New Europe (Saarbrücker Rede über das Neue Europa). It was Döblin’s last public address and a powerful statement for a strong, peaceful and united Europe:

“Europe! [….] The current state […] is actually unworthy of the men and women who live here, in fact we are all Europeans, whether we speak German, French or Italian. But it doesn’t matter, tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, we have to confront each other again, because the border runs like this and the other runs like that, and we would have to put ourselves on this side or on that [….] The old state systems have lost their meaning, Europe is the reality of today [….] Show them that behind the old rusty reality there is a young and splendid new one. Show the power you have to tear down the old structure. Team up! No small slogans. The just fight, the true fight, the only fight. ” (Translation T.H.)

It would be the right time today to remember this encouraging call for peace and unity in Europe!

The reviewed volume is excellently edited. It contains a long and instructive afterword by Ralph Schock, the editor of the book, as well as references and a bibliography. Particularly noteworthy are the many historical photos from German and French archives; they make the numerous connections of Döblin to the German-French border region also visually tangible. The book has a hard cover with dust jacket, a bound-in book sign and is carefully bound and printed on good, acid-free paper. It was published in a series “Spuren” (Traces) of a regional small publishing house (Gollenstein), which illuminated the literary references of significant authors to the Saar region in outstanding editions. I have for example discussed a volume of Joseph Roth’s journalistic work in the past that was published in this series; other volumes are dedicated to Hermann Hesse, Philippe Soupault, Ilya Ehrenburg, Theodor Balk, Francois-Régis Bastide, or Harald Gerlach. It is a pity that the publisher has now disappeared from the scene without a trace.

Admittedly, this was a contribution that went well beyond the average length of my usual book reviews. This is mainly due to this really beautiful book itself, which I read with particular interest not least because of my own origin from this region. In addition, I learned many details from the life of Alfred Döblin, that were previously unknown to me. Although an English translation of this volume is very unlikely, I still hope that especially Berlin Alexanderplatz readers may find this article useful. And maybe a few readers will try one of the other translated, but rarely read books by this author. Döblin’s oeuvre is full of surprises; in any case it is worth discovering this interesting author!

Alfred Döblin: “Meine Adresse ist: Saargemünd”, Gollenstein 2009; Je vous écris de Sarreguemines, tr. Renate and Alain Lance, Serge Domini Editeur 2017

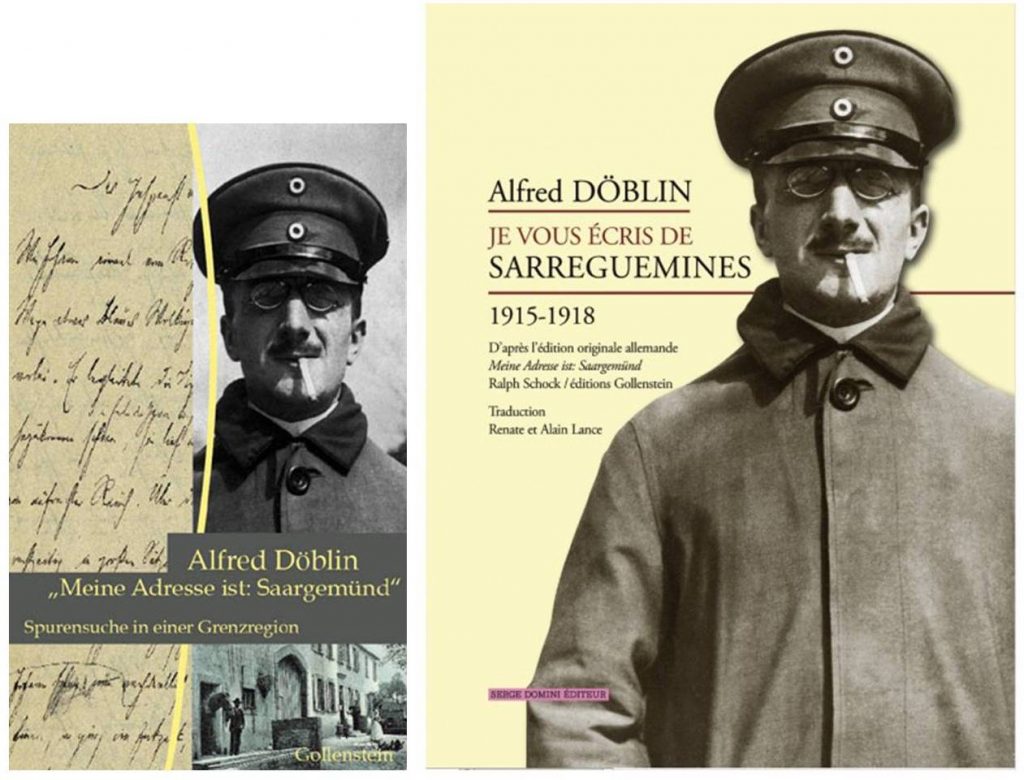

Marc Petit: L’équation de Kolmogoroff. Vie et mort de Wolfgang Doeblin, un génie dans la tourmente nazie, Ramsay 2003, Folio 2005; Die verlorene Gleichung. Auf der Suche nach Wolfgang und Alfred Döblin, Eichborn 2005

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-9. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter