In this second part of my short series about Bulgarian Poetry collections available in English translation, I will cover the period until 1944, the year of the Communist takeover in Bulgaria. While in the last blog post I was presenting anthologies, I will focus in this post on books that present the (selected) poems of a single author.

The years before 1944 were a rich period for Bulgaria’s poetry. And quite a lot of it has been translated at one point in English: in the Communist era, the state-owned publisher Sofia Press made most of the “classic” Bulgarian poets available in English (and some other languages). These books are of course out-of-print since a long time, but due to the lack of any later editions in English for many of the most relevant authors, they are still worth to be searched in antiquarian bookstores or internet platforms. I would particularly recommend – if you can find them – the volumes with Hristo Botev’s Poems, and Ivan Vazov’s Selected Poems. Both of them can be considered as founding fathers of Bulgarian literature. Other editions by Sofia Press include Selected Poetry and Prose by Hristo Smirnensky and The Road to Freedom by Geo Milev.

The good news is that in the last years three important Bulgarian poets from this period are again present with a book in English language.

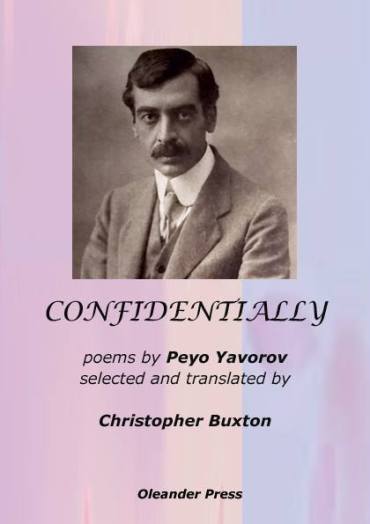

Peyo Yavorov (b. 1878, Chirpan – d. 1914, Sofia) was, especially in his more mature years as a poet, a protagonist of the symbolist movement in Bulgaria. But at the same time, the man who wrote highly introspective poems, and verses that show great empathy for the lives of refugees from Macedonia and Armenia, was a man of action: just like Botev a few decades earlier, he joined the struggle for liberation from the Ottoman domination, in his case in Macedonia; the poet-partisan was – after his first big love died from tuberculosis – married to Lora Karavelova, the daughter of the former Prime Minister Petko Karavelov. But the marriage didn’t last long: in a bout of jealousy, Lora shot herself in front of Yavorov, and the poet committed suicide one year later, after a first attempt to take his life had left him blind, and a press campaign against him, even suggesting that he had murdered his wife, had made him a broken man. A collection of his poems (Confidentially, Black Sea Oleander Press 2018), skilfully translated by Christopher Buxton, gives the Anglophone reader an opportunity to get an idea of Yavorov’s remarkable gifts as a poet (more is not possible in any translation of poetry).

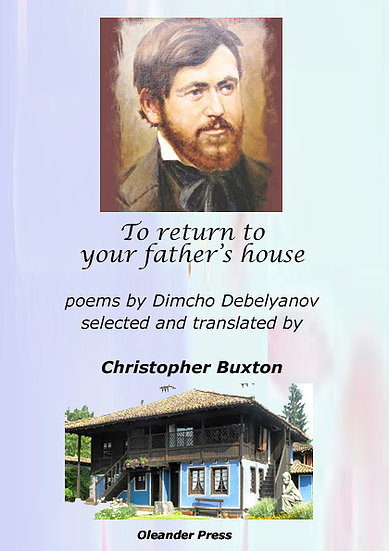

Dimcho Debelyanov was a few years younger than Yavorov, but also his life was – like the lives of so many Bulgarian poets – cut short, in his case by WWI: he was killed in battle in 1916. Debelyanov, only 29 years old at the time of his death had moved from the symbolism of his youth to a more realistic style of poetry. Debelyanov is considered a master of the elegy, but in many of his poems there are also satirical elements. He was also a gifted translator from English and French. As in the case of Yavorov, Christopher Buxton is also here the translator, editor and publisher of a collection of Debelyanov’s poems (To return to your father’s house, Black Sea Oleander Press 2017), and to me this work seems similarly congenial as his Yavorov translations. I can recommend both books warmly, in any case these are two very welcome additions to the Bulgarian poetry shelf, and I hope there will be even more from this source in the future. The book cover shows a portrait of the poet and his birthplace, now a museum, in Koprivshtitsa, one of the most well-preserved old towns in Bulgaria and in any case worth a visit.

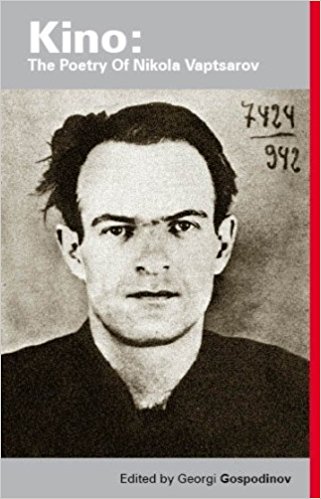

Nikola Vaptsarov (b. 1909, Bansko – d. 1942, Sofia) was a trained naval engineer, who after years on ships in the Mediterranean, worked as an engineer in various factories and at the Bulgarian Railroad. He got involved with the Communist Party for whose military faction he secretly supplied arms for the resistance fight against the Germans; a dangerous activity, and Vaptsarov was finally arrested and executed by firing squad. During his lifetime, he published only one book, Motor Songs (1940) (under pseudonym). The concrete, colloquial poetry of Vaptsarov that includes reference to cinema, radio, technology, and modern culture, is widely unknown outside Bulgaria (although he was translated in 98 languages). Yannis Ritsos, the great Greek poet said about him:

“I consider Vaptsarov my brother in poetry and struggle.”

A slender volume, edited and introduced by Georgi Gospodinov, competently translated by Kalina Filipova, Bilyana Kourtasheva, and Evgenia Pancheva is available under the title “Kino” (Smokestack Books, 2014), and it is very much worth to be discovered by a wider readership. (The cover shows a mug shot of Vaptsarov, taken after his arrest.)

Yavorov, Debelyanov, Vaptsarov (and one could add Botev and Milev as well): all died young and not of natural causes. It’s a rather sad thought to imagine what they could have achieved, if their lives had not been cut short…

This review was first published at Global Literature in Libraries Initiative, 08 June, 2018 for #BulgarianLiteratureMonth.

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-8. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter