Samuel Beckett is one of the most discussed and reviewed authors of the 20th century. The pessimistic, often hopeless view of the world that the author shows us in his work appears unbearable at first glance, but the apparent senselessness and absurdity of existence is softened by the black humor typical of Beckett.

For the audience of his pieces in the 1950s, this was an unusual, and for many also shocking, approach. Beckett, the deeply private and shy man, unwillingly turned into an existentialist author par excellence – even if he rightly saw himself as a literary loner – his plays became enormous theatrical successes, their author received the Nobel Prize (one of the few cases in which the committee in Stockholm was right), in many countries his work is read in school and the author has become a modern classic.

So, there is nothing more obvious than making Beckett the subject of a modest blog post. Especially since Beckett was – and is! – a very important author for my own intellectual development. And because, after everything I know about him, he must have been a very likeable person. As is well known, this is something exceptionally rare among writers …

Since so incredibly much has been written about Beckett’s works – comparable only to Kafka in this respect -, it is difficult for me to choose one of his works for a review. The danger of repeating something that some other and possibly more erudite mind has already written in a more interesting way seems too great to me.

Instead, a few lines will follow about a book that deals with a certain, rarely noticed, but nevertheless very important aspect of Beckett’s work: his relationship to Germany and to the German language and culture.

From November 2017 to July 2018, an excellent exhibition entitled German fever, Beckett in Deutschland took place at the Literaturmuseum der Moderne (Modern Literature Museum) in tranquil Marbach am Neckar in Germany. Documents from various archives and collections were made available to the public for the first time in an excellently curated form, including the so-called German Diaries, Beckett’s notes during his extensive trip to Germany from September 1936 to April 1937.

Marbach, Schiller’s birthplace, is the seat of the Deutsche Schillerstiftung (German Schiller Foundation) and the Deutsches Literaturarchiv (German Literature Archive), in which the bequests (and pre-bequests) of many German authors are stored and scientifically edited. In addition to various other series of publications of these institutions, the Marbach catalogs and the Marbach magazine appear on a regular basis. They showcase and document the exhibitions of the museum. A fantastic treasure trove for anyone interested in German literature and I can also highly recommend a visit to the museum itself.

The double volume of the Marbacher Magazin discussed here contains, in addition to the carefully compiled catalog section with images of the exhibits and their transcription and explanation, a longer essay by the authors of the volume, Mark Nixon and Dirk Van Hulle. The result is an attractive volume of almost 250 pages. It is particularly gratifying that the band is bilingual (German / English).

In the summer of 1928, the young Beckett – at that time a poorly paid lecturer in Paris who was working on his first publications and occasionally assignments as an assistant and researcher for James Joyce – met his cousin Peggy Sinclair during a stay in Dublin and fell in love with her. At the end of August, Beckett traveled to Kassel for the first time, where Peggy lived with her parents, who were tremendously interested in art. Even before meeting Peggy, Beckett had begun to systematically study German literature and to learn German.

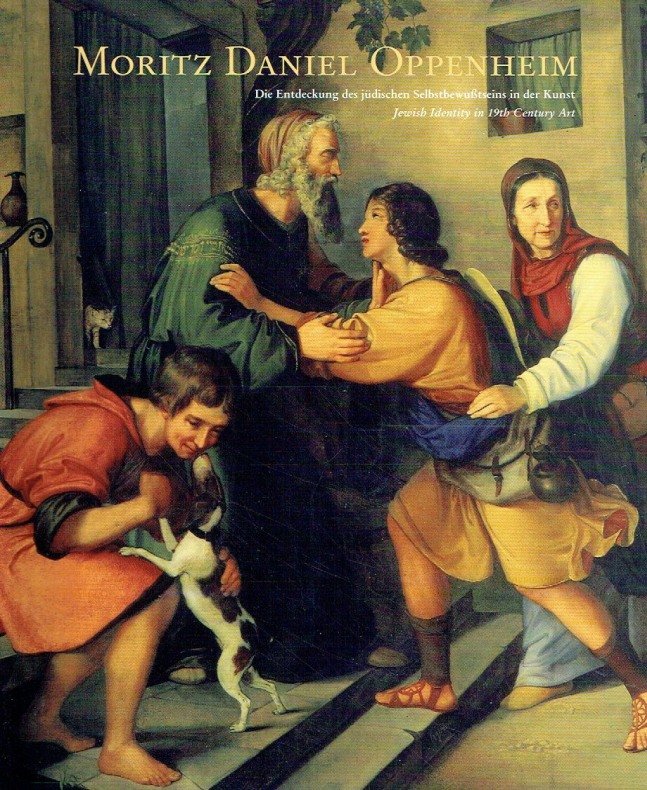

In the period up to 1931 there were numerous, sometimes extensive, visits to Kassel. Beckett was a welcome guest with the Sinclairs, who introduced the cultured young man to German-language literature and music. Peggy’s father was an art dealer and found in Beckett an inquisitive listener who, under the influence of the experienced Sinclair, got more and more interested in German art. Beckett was particularly fond of Dürer and his contemporaries, but also in contemporary art. Additionally, he used his stays in Germany to improve his German language skills and to deal more systematically with modern literature.

It may come as a surprise that Beckett’s all-time favorite novel (and not just in German) was Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest. Even in later years he read the novel again and again with never-ending enthusiasm and recommended it to friends and colleagues. The fact that Effi Briest was also Peggy’s favorite novel may have played a role here, although admittedly it is an excellent novel.

Of course, Beckett also read the classics Goethe and Schiller. While he was not particularly impressed by Schiller, whom he found slightly too emotional and idealistic, he valued Goethe far more – which did not prevent him from breaking off reading Goethe’s Faust at a certain point. On the other hand, he was enthusiastic about Walther von der Vogelweide and especially Hölderlin, who was much closer to him as a person than the classics.

Beckett’s love affair with Peggy ended as early as 1929, but his regular visits to Kassel lasted until 1931. In 1932 he visited Peggy, then terminally ill with tuberculosis in a sanatorium in Bad Wildungen. Peggy died there a year later, just 22 years old. Beckett processed his experiences in Kassel in his novel Dream of Fair to Middling Women, which was written at the time but was only published posthumously.

In addition to art and literature, philosophy also played a major role for young Beckett. For Joyce, who was working on Finnegans Wake at the time, he tracked down a volume of Fritz Mauthner’s work on the critic of language. It would be an interesting subject to examine Mauthner’s influence on Beckett’s work, which should not be underestimated. For Beckett, Schopenhauer’s pessimistic worldview became an antidote to the idealism of the German classics. In addition to Hölderlin’s Gesammelte Werke (Collected Works), Beckett also acquired the entire Schopenhauer in German and kept both editions throughout his life, reading and annotating them extensively.

Beckett was rather active as a writer in the 1930s, but much of what he wrote remained unpublished until after his death. During this time Beckett was more and more in doubt as to whether it was even possible to adequately express his thoughts in English. In addition to the influence of language-critical philosophy and a French-speaking environment, the fact that Ireland – and the English language associated with it – was traumatic for him also played a role. His recurring painful arguments with his mother, a woman who can easily be imagined in a play by Strindberg, also made it appear necessary for Beckett to radically free himself from this influence by “emigrating” into another language. The natural choice for this was French, although the exhibition makes it clear that Beckett also attempted writing in German.

In this situation critical for his development, Beckett undertook an extended trip to Germany, which he documented meticulously in diaries, the originals of which were also shown in the exhibition. From September 1936 to April 1937 he visited Hamburg, Berlin, Dresden, Halle, Weimar and Munich, among others.

The journals of the trip are on the one hand extremely interesting because the foreign visitor recorded and commented on the situation in Nazi Germany without illusions, but on the other hand they also provide information about the aesthetic development that Beckett went through during this time. In every city he visits he has a plan of which museums and exhibitions he wants to visit, he takes notes, finds intellectuals who quite openly flaunt their disgust for the Nazis. Occasionally, persuasion and a small bribe also helps to see works of the so-called degenerate artists, which, however, are also shown in special exhibitions by the Nazis – before these works are destroyed, sold or hidden in some storage room. Beckett knows it will be the last opportunity in a long time to see it all all over again. Here, too, it would be interesting to demonstrate in detail how Beckett was influenced in the post-WWII stage designs he had in mind for his plays by the art that he experienced during these years, especially during his visits to Germany.

A special surprise for me was the information that Beckett wrote his first play Mittelalterliches Dreieck (Medieval Triangle) in 1936 – in German! The play remained a fragment, but it becomes clear that Beckett toyed with the idea of becoming a German-writing author. He also translated his poem Cascando into German and created long lists of German words that document his seriousness with this undertaking.

Beckett, who had joined the French Resistance during the occupation of the country, soon sought contact with Germany again after the end of the war. With the publishers Peter Suhrkamp and later with his successor Siegfried Unseld he established a relationship that lasted for decades and that went well beyond the usual author-publisher business relationship. This relationship was to become of central importance for the worldwide outreach and success of his work. Beckett’s plays appeared in a trilingual edition (French / English / German), an idea that appealed tremendously to Beckett. It is also significant to note that Beckett played a major role in the German translation, which was a real co-production. Beckett was not very satisfied with Elmar Tophoven’s first attempts at translation and suggested that the young man, who was just in Paris, visit him and work on the translation together. The manuscripts in the exhibition show how painstaking Beckett’s work with the translator couple Elmar and Erika Tophoven was.

A nice character trait of Beckett was his personal loyalty and integrity. He made for example sure that “his” translators should translate everything from him and he also campaigned for this at Suhrkamp, his publishing house. Although Beckett was an extremely meticulous worker to whom every detail was important, the correspondence, especially between Beckett and Unseld, is warm and friendly, even amicable. Although both men were known to be averse to sentimentality, Unseld, who immediately recorded important writers’ meetings afterwards, was visibly touched when the seriously ill Beckett kissed him on both cheeks when they last met. (I imagine Unseld had to see Thomas Bernhard after that, and anyone familiar with the Unseld-Bernhard correspondence knows that Bernhard was infinitely more difficult to deal with).

The last two chapters of the catalog deal with Beckett’s work as a theater director of seven(!) of his own plays with the Schillertheater Berlin and his collaboration with the Süddeutscher Rundfunk on various television productions. Here, too, Beckett shows himself to be a hard worker, who always goes to great lenghts to prepare himself precisely, who learns his plays by heart in German and also uses German to a large extent at work. For each of his productions, he wrote a separate director’s book beforehand with detailed comments on the planned production. Occasionally he also changes little things in the text, still tweaking every little formulation. And again remarkable: his friendly treatment of a well-coordinated team that he trusts, above all his favorite actors Horst Bollmann and Stefan Wigger. His openness to the new medium of television and the possibilities it offers – and the freedom that Süddeutscher Rundfunk gives him for it – is all very well documented in this beautiful catalog book.

German fever opens up an unfamiliar view of an author you think you know. A book that I can recommend to anyone who is even a little interested in Samuel Beckett and his work. Kudos to the people in Marbach and elsewhere who make such meaningful exhibitions and publications possible.

Mark Nixon/Dirk Van Hulle: German fever. Beckett in Deutschland, Deutsche Schillergesellschaft, Marbach am Neckar 2017, Marbacher Magazin 158/159

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-22. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter