Norman Tweed Whitaker, the “hero” of this biography is a Dickensian figure: he was both, full of genius and a devil at the same time. Coming from an educated upper middle class family – his father was a high school principle in Philadelphia – Whitaker (1890-1975) became a patent attorney that held also a degree in German literature; his great talent as a chess player made him a dangerous opponent for any player and earned him the US Master title and in 1965 the title of an International Master (that was before the “title inflation” when this title meant still a lot).

Among the masters he defeated in serious games were the legendary players Frank Marshall, David Janowski and Samuel Reshevsky, for decades America’s strongest player (all of them were contenders for the World Championship title); in simuls he even won against Emanuel Lasker and the young Capablanca. The book contains more than 500 games played by Whitaker, some of them annotated. Whitaker was a dangerous tactician with a good endgame knowledge, but the patience for positional play was something he obviously lacked – a mirror of his personality maybe.

Also as a chess promoter Whitaker did more than probably anybody else in the United States for decades to make the game popular: he gave countless exhibition and simultaneous games, organized tournaments, raised funds, worked as a trainer and founded chess clubs, traveled a big deal in the U.S. and abroad to promote the game, co-authored a chess endgame book – and quarreled a lot with the U.S. Chess Association and people who prevented him to earn the recognition he thought he deserved. He saw himself frequently as a victim of some conspiracy of vicious people that used the threat to expose very personal information about him in order to discredit him and to sidestep him whenever it was possible for them.

This all may be not particularly interesting outside the very specialized circle of chess players or those interested in chess history. But there is an element in this biography that makes it interesting for a wider audience. Whitaker, the cultivated, well-educated patent attorney from a good family and with the chess interest and talent was also a ruthless con man with a long criminal record.

Whitaker was convicted for crimes such as interstate car theft, insurance fraud, extortion and blackmailing (he claimed to know the whereabouts of the kidnapped and murdered Lindbergh baby and was arrested when he tried to extort money for allegedly returning the baby), selling morphine and other drugs via mail, and finally also child molesting. (This list is not complete.)

Grandmaster Arnold Denker who knew him well said about Whitaker:

“His advanced education, high intelligence, command of foreign languages, expensive wardrobe, plentiful ready cash, skill at chess, and confident personal manner all aided in fooling many unsuspecting victims.”

A criminal “career” that spanned over several decades and that earned him various convictions and many years in the jails of Leavenworth and Alcatraz. Therefore it is not surprising that in this well researched and written biography by chess historian John S. Hilbert not only chess masters, but also the Lindbergh family, J. Edgar Hoover and Al Capone (with whom he made friends while serving time in Alcatraz) play a certain role.

What turns a talented, intelligent and rather successful man with a good profession into a criminal? And how did this part of his personality coexist with that of a serious, energetic chess promoter with good contacts in many places? The rather unsettling and surprising answer is: we don’t know. There is no warning sign, no early childhood trauma, no history of being depraved of love and affection by his family that turned Norman T. Whitaker into the ruthless criminal he was. It seems that after the first arrest in 1921 and the following conviction – which was so shocking to his father that he died of a heart attack when he learned about the car theft – Whitaker’s life was like on an inclined plane from which there was no turning back.

An interesting book not only for chess players – thanks to the author’s clever choice of documents and his ability to present us his subject as a person with such contradictory characteristics that they hardly seem to fit into one human being, we get to know a fascinating, weird personality.

„What is it in us that lies, whores, steals, and murders?” (Georg Büchner: Danton’s Death) – that enigma remains still unresolved.

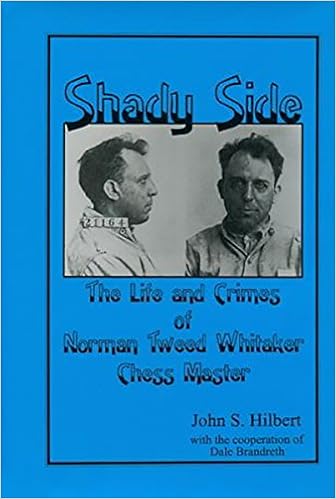

John S. Hilbert: Shady Side: The Life and Crimes of Norman Tweed Whitaker, Chess Master, Caissa Editions, Yorklyn 2000 (ed. Dale Brandreth)

Arnold Denker: Stormin’ Norman, in: ibid, The Bobby Fischer I Knew And Other Stories, p. 262-274, Hypermodern Press 1995

Norman T. Whitaker / Glenn E. Hartleb: 365 Ausgewählte Endspiele: Eines Für Jeden Tag Im Jahr, Selbstverlag, Heidelberg 1960

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter