The hero – if I can call him that – and narrator of Bartleby & Co., a novel by the Spanish author Enrique Vila-Matas, is a failed writer who had published as a young man a novel on the impossibility of love. As a result of a personal trauma and the reaction of his surrounding to the publication of the book, he has become silent as an author, a modern Bartleby that spends most of his uneventful life in an office.

A misheard remark of a colleague (“Mr. Bartleby is in a meeting”.) triggers in him again an urge to write – a novel in the form of footnotes on the representatives of what he calls “the Literature of the No”, a collection of aphorisms, short musings and essays, glimpses of personal memories, quotations from phone conversations with a friend or from letters of a writer, and recollections of meetings with other authors.

The 86 footnotes that form the biggest part of the text circle around those authors who at a certain moment in their lives “preferred not to” write any longer, and whom the narrator considers as brothers (although also a female author plays an important role, the “Bartleby syndrome” seems to be by far more widespread among male writers.).

The dull and uneventful life of the narrator, together with his tendency to bath sometimes in self-pity are frequently contrasted by remarks that made me smile. A good example which is typical for the “sound” of the book are the opening lines:

“I never had much luck with women. I have a pitiful hump, which I am resigned to. All my closest relatives are dead. I am a poor recluse working in a ghastly office. Apart from that, I am happy.”

The modern “Literature of the No” dates back to the 19th century when the two American writers (and friends) Melville and Hawthorne created their stories Bartleby the Scrivener and The Vicar of Wakefield, two stories about a rejection that in many ways foreshadowed

“future phantom books and other refusals to write that would soon flood the literary stage.”

In his footnotes, the narrator explores famous examples of the “Literature of the No”, such as Robert Walser or Kafka; and while suicide or mental insanity seem to be among the most popular “strategies” for the Bartlebys among the authors, they are not held in particular high esteem by the narrator. He is definitely more interested in those cases where an author, while still alive simply disappeared from literature.

One of the most interesting things about the book is the abundance of examples of authors that are introduced to us readers; while I read many of them and know a few others by name, I discovered also plenty of seemingly extremely interesting writers particularly from the Spanish-speaking literature (mea culpa that I am not so well read in Spanish literature as I should considering the richness of this literary continent) who have fell silent at a certain moment in their lives. Felisberto Hernandez for example was not an author I had on my radar until now, but I will definitely look up what I can find about him. Another interesting author “without a work” is the Italian (non-)author Bobi Bazlen, whose name I came across once in Claudio Magris’ books about Trieste.

I can imagine that one of the most annoying questions for an author must be the following: “What are you writing right now? On what are you working?”; or to an author who hasn’t published anything since a long time: “Why don’t you write again? What is the reason for your silence?” One of the best answers for me to the latter question is that of Juan Rulfo, an author for whose slender work I have the highest admiration:

“Well, my Uncle Celerino died and it was he who told me the stories.”

Not that this Uncle Celerino was an invention, he had really existed and was known as a big storyteller – but there must have been something else behind the silence of Rulfo, something about which he rather preferred not to speak.

Our narrator gives us also some examples of his own experience and research that includes a chance meeting with J.D. Salinger in New York, a visit at Julien Gracq’s home, but also personal memories about his childhood friendship with Luis Felipe Pineda, or his infatuation with Maria Lima Mendes, a very impressive example of a female representative of the “Literature of the No” (and possibly made up by Vila-Matas).

Hölderlin, Chamfort, Rimbaud, Larbaud, Hofmannsthal, Fernando Pessoa, Juan Ramon Jimenez, and many others make an appearance in these footnotes. And although as a reader we will not resolve in a single case the true reason for the silence of an author, we will have experienced an abundance of witty, comical, tragic, interesting anecdotes, stories, musings when we have finished this – obviously well-translated – book.

The narrator of this book (and its author) deserve a place at the Olympus of writers and non-writers of books. Who is able to write wonderful ironic passages like this one:

“I’ve worked well, I can be pleased with what I’ve done. I put down my pen, because it’s evening. Twilight imaginings. My wife and kids are in the next room, full of life. I have good health and enough money. God, I’m unhappy!

But what am I saying? I’m not unhappy, I haven’t put down the pen, I don’t have a wife and kids, or a next room, I don’t have enough money, it isn’t evening.”

and who is granting his happy-unhappy and rather unreliable narrator the equally ironic luck to complete this wonderful book about authors who fell silent, must be a great author himself. My first book by Vila-Matas, and for sure not my last.

P.S. And what about those who wrote, but were rejected by too many publishers, and who therefore gave up on being published? Also here, our narrator is helpful. Send your rejected manuscript to the Brautigan Library, the brainchild of underground author Richard Brautigan, nowadays hosted at the Washington State University Vancouver.

“The Brautigan Library accepts exclusively manuscripts that, having been rejected by the publishers who were sent them, were never published. This library holds only aborted books. Anyone with such a manuscript, wishing to submit it to the Brautigan Library or Library of the No, need only pop it in the post … I have it on good authority – though there they are only interested in bad authority – that no manuscript is ever rejected; on the contrary, there they are looked after and exhibited with the greatest pleasure and respect.”

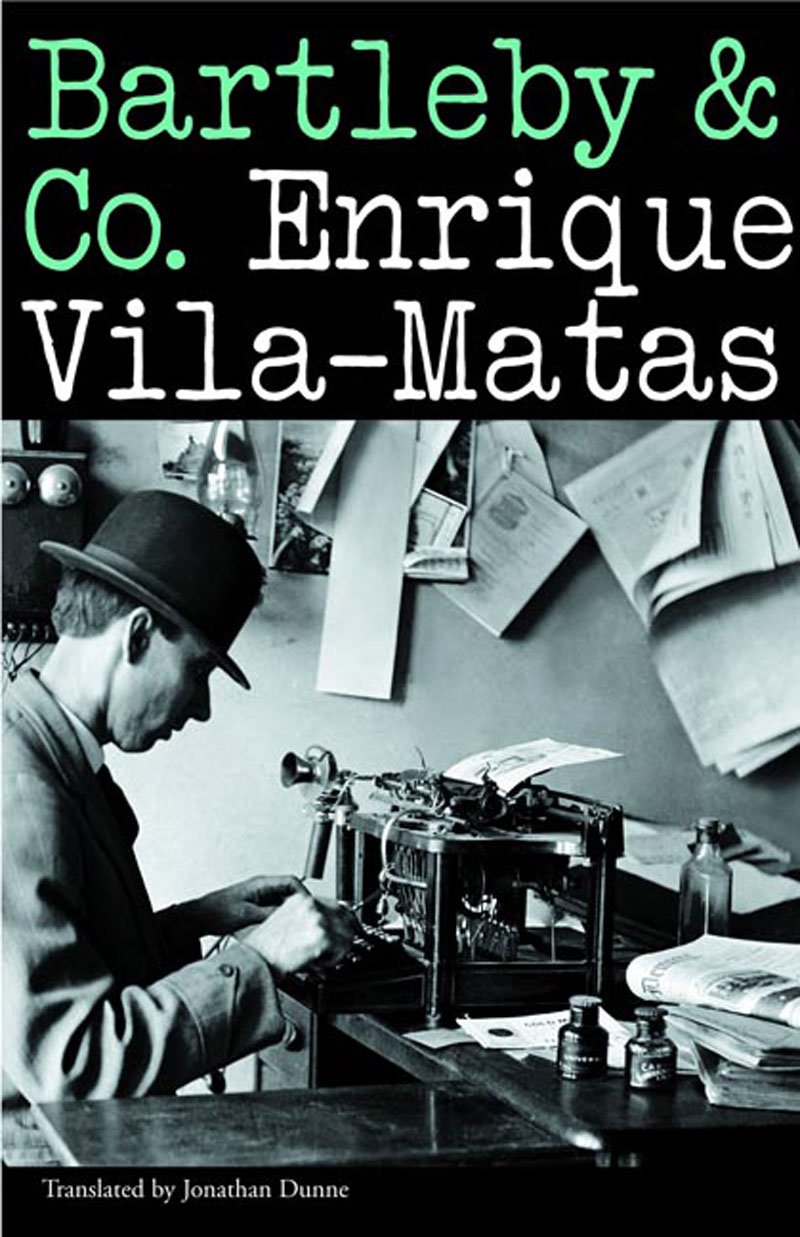

Enrique Vila-Matas: Bartleby & Co., translated by Jonathan Dunne, New Directions, New York 2004

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter