The territory of what is today the Republic of Bulgaria was for more than five centuries part of the Ottoman Empire and I think it is fair to say that the fight for liberation from what Bulgarians call either the “Ottoman Yoke“ or “Ottoman Slavery” is until today a defining moment for the identity of most ethnic Bulgarians.

Nations are, as Benedict Anderson puts it in his famous book, “Imagined Communities”. And the community called “Bulgarians” is defined not so much by historical events as they really took place, or by what certain historical figures (such as Vasil Levski or Hristo Botev) really did, and by what it meant in a strictly historical perspective, but more by the image Bulgarians have of these events and personages, the narrative that they learn in school or via the media. Hence the trend to mythologize the fight for liberation in the 19th century, hence the permanent exaggeration and distortion of certain historical facts, and the glossing over of others that don’t fit in the narrative that is generally accepted, but that is maybe not factually accurate. This is of course nothing specific to Bulgaria, it could be said for the national identity of all nation states: they are based on these kind of “constructs”. I have at least read a dozen Bulgarian novels, starting from Ivan Vazov’s “Under the Yoke”, to Anton Donchev’s famous (many say infamous) “Time of Parting”, to the remarkable more recent novel by Milen Ruskov “Uprising”, that deal in one way or the other with the liberation fight, or the relation of Bulgarians and Turks in the time of the Ottoman Empire. And the same can be said of Bulgarian Cinema: three of the biggest Box Office hits of the last years had exactly the same topic – the Bulgarian liberation fight in the 19th century.

But while these events that are formative to the Bulgarian identity seem to be part of the distant past, Bulgarians and Turks live still together in today’s Bulgaria. The material heritage of the Ottoman Empire, in the form of the remaining buildings from that time, as well as the people of Turkic origins (Turks, Gagauz, Tatars) that are living in comparatively peaceful coexistence with their ethnically Bulgarian neighbors in the country, are present, not past. When I say “comparatively peaceful” it means that there have been conflicts, especially in the time of communism when a ruthless policy of forced assimilation was introduced: Muslims (including Roma and Pomaks), as well as the non-Muslim Gagauz had to change their names, celebration of religious feasts was banned as well as the speaking of Turkish, and hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian citizens of Turkish origin were forced to leave Bulgaria and were stripped of their citizenship in 1989, just a few months before the (formal) end of communism rule in Bulgaria. A wave of terrorist acts (at least some of them perpetrated by the communist State Security) and self-immolations took place in the 1980’s, and while after the changes in the 1990’s these people were at least given back their citizenship and their own names, the relation between ethnic Bulgarians and Turks remains still strained and is frequently used by different political groups to incite ethnic unrest or even hatred.

As a country with great religious and ethnic diversity, Bulgaria should consider its material heritage from the Ottoman times as well as the diversity of people, ethnicities and religions that live in the country and are Bulgarian citizens as a treasure, not as a threat to some old-fashioned concept of nationalism.

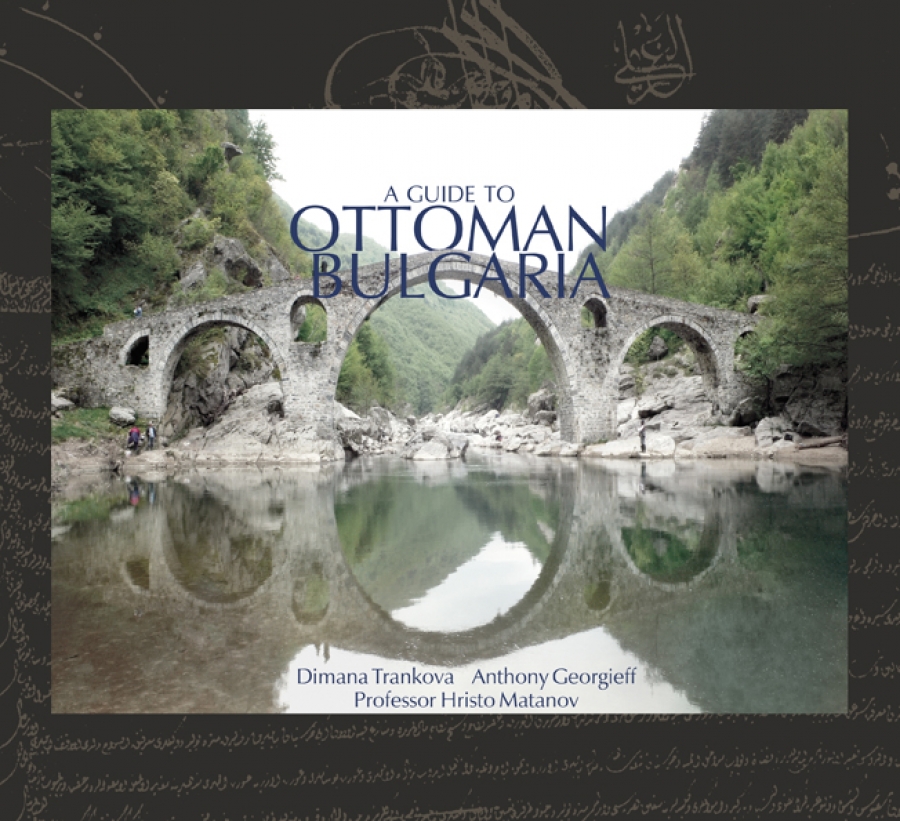

For English-speaking readers I can heartily recommend two books that deal with the Turkish/Ottoman heritage of Bulgaria. A Guide to Ottoman Bulgaria by Dimana Trankova, Anthony Georgieff and Hristo Matanov (Vagabond Media 2012) takes the reader on a journey all over Bulgaria that leads to the mosques in Sofia, Samokov, Shumen, Plovdiv, Razgrad and Stara Zagora, but also to lesser known Ottoman buildings and traces in Gotse Delchev, Vidin, Ruse, Silistra, Belogradchik, Varna, Suvorovo and Uzundzhovo. A special chapter deals with Ottoman bridges (bridges similar to those described in Ivo Andric’s Bridge over the Drina or Ismail Kadare’s Three-Arched Bridge), and also with Ottoman fountains and abandoned mosques. The combination of highly knowledgeable text and beautiful photographs makes this book much more than another coffee table book. I am quite sure that most readers of this book will feel tempted to immediately undertake a tour to some of these buildings. The cover shows the so-called Devil’s Bridge at the Arda River in the Rhodopes.) Some photos from the book can be found here.

While the previous book deals with the material heritage of the Ottomans, The Turks of Bulgaria (2012) is about the non-material heritage of the Ottomans in Bulgaria, the people and their history and culture. Chapters on history, including the forcible Bulgarisation campaigns against Turks already mentioned above; culture; folklore; religion; cuisine; music and dance; language. There is a detailed chapter on Pomaks (Bulgarophone Muslims) and Gagauz (Christian Turks), and the book is like the first one richly illustrated.

Vagabond Media is doing a terrific job in documenting the immense cultural heritage of Bulgaria in beautiful editions that combine high-quality photography with excellent essays that guide the reader. Titles like “A Guide to Jewish Bulgaria”, “The Bulgarians” (a book that I reviewed some time ago here), “A Guide to Thracian Bulgaria”, or “A Guide to Communist Bulgaria” , to mention just a few, make people aware what an incredible cultural richness Bulgaria represents, but they also document buildings that are frequently endangered and in disrepair. And in some cases, like with many of the buildings from Communist Bulgaria, it is rather obvious that in a few years’ time, all that will remain from them will be photos and books.

In any case, the books of Vagabond Media (and the high-end journal Vagabond too) are an excellent source for anyone with an interest in Bulgarian culture and architectural heritage.

This review was first published at Global Literature in Libraries Initiative, 12 June, 2018 for #BulgarianLiteratureMonth.

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-8. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter