E.V. is the Remedy Man in the short story with this title that opens the collection Great Dream of Heaven. He is a kind of horse whisperer who is called by Mason, a farmer somewhere in the West of the U.S. when one of his particular wild horses cannot be tamed. E.V., a rather unassuming man, knows his trade and we readers witness how he is resolving the problem while chatting casually with Mason and inviting Mason’s son, who is also the narrator of the story to assist him. In the end we have learned a few things about horses and about life on an isolated farm in the West. So, what – you will maybe feel inclined to say.

But there is more to this story than just this. While usually the father, a well-meaning, but dominating figure is the one who sets the rules for the son (women are absent in this story), it is this one time E.V. who tells the son in a friendly, casual way what to do next in order to help him – while the father is a quite passive bystander, strangely skeptic about E.V.’s remedy man’s work that proves to be successful. For the son, this is a new experience: to see his father passive and another person being in charge. In the end, the narrator watches from a tree the evening and night sky:

“The whole ranch turned below me. I arched my head back and my mouth went open to the black sky. The giant splash of the Milky Way must have caused the high shrill squealing to burst out of me, just like someone had pulled a cord straight down my spine. My skin was laughing. I heard my dad come out on the screen porch and yell my name but I didn’t answer. I just hung there spinning in silence. I knew right then where I’d come from and how far I’d be going away.”

The heroes of these stories are frequently on the move, like the man who left his wife to live with his new love (in Coalinga ½ Way). He stops in some godforsaken place called Coalinga, halfway between the place he lived and the place he intends to live. It’s revealing that it is the perfect equidistance between the two important women in his life. When he calls his wife from there, she tries to convince him to come back, or at least meet somewhere to discuss what is wrong with their relationship in person. But even the fact that he is not only leaving his wife for good, but also his son who is still a little child, cannot make him change his mind.

“What about Spence? Are you going to tell him you’re not coming back?” – “Not right now.” – “When?” she says. – “I don’t know.” – “What am I supposed to tell him then?” – “Tell him I’ll call him.” – “When?” – “I’m not sure.” – Silence again. A high piercing shriek of a circling hawk. A Jeep roars past. A Jeep with no windows or doors, just the wind ripping across the wide-eyed face of the driver. – “Are you still there?”, he says to the phone. – “Where am I supposed to go?” she says. – “I don’t know.”

After he hangs up, he is calling his lover with whom he intends to live in the future. But this woman tells him not to come. It turns out she is moving to Indiana with her husband and considered the relationship with the narrator as a fling without much importance. The end mirrors the conversation he had just before with his wife, but with reversed roles:

“You’re flying out to Indiana to meet David?” – “Yes. I was just going out the door when the phone rang.” He hears the loud splash of the fat man hitting the pool outside. Then nothing. A distant siren. “Hello,” she says. “Are you still there?” – “Where am I supposed to go?” he says.

These two stories contain a lot of elements that are typical for this book. A man between two women, or a woman between two men. The physical distance, but also the rift between people in general, and the gulf that separates people from their true selves. The setting is usually in a small town, or somewhere on the road (like in Blinking Eye, where a young woman drives thousands of kilometers with the urn that contains the ashes of her mother). Men have problems with women and with themselves, frequently because they cannot find the right words to express their feelings or leave the important things unsaid. Paranoia is frequently just around the corner (The Company’s Interest), and when firearms come into the picture, things threaten to get out of control very fast (An Unfair Question).

There is also a dry humor in many stories (like in It Wasn’t Proust, or in The Door to Women). The dialogues (Betty’s Cats consists exclusively of dialogues) conceal the experienced playwright and film scenarist and seem to be written with an effortless ease. These are real people talking, and their loneliness is always present, just like in the paintings of Edward Hopper, of which they reminded me sometimes. Or as in the movie Paris, Texas by Wim Wenders. And that’s no coincidence, because Shepard wrote the script of that film. (He is also a remarkable actor – The Right Stuff, Fool for Love, Homo Faber, Don’t Come Knocking come to mind.)

I enjoyed these wonderful stories very much. My favorite piece is the title story Great Dream of Heaven. But they are all very good, without exception.

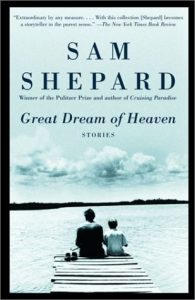

Sam Shepard: Great Dream of Heaven, Vintage, London 2003

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter