The autobiography of Booker T. Washington Up from Slavery is an interesting book for various reasons. It belongs to the small group of works written by black men in the United States that were born as slaves and who later gave witness regarding their lives as slaves and thereafter (i.e. after the end of the Civil War, when slavery was officially abolished in the South). Other works of this genre include Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, and Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

But apart from being a very interesting document in itself, the book is also interesting until today because Washington was the first black leader in the U.S. to address big audiences in the North and the South, black and white alike, a man with a mission – he founded the Tuskegee Institute (today Tuskegee University) in 1881, the first school in which black teachers were trained and students had a chance to learn also professional skills that would prove to be the economic basis for the further social development of the black population in the South.

Washington was probably born in 1856, the exact date and month are not known. He grew up on a farm in Virginia in very basic conditions although the slave holding family seems to have treated their “property” comparatively well. The chapters in which Washington describes his childhood on the farm and the time after the end of the Civil War, when the family moved to West Virginia, are very touching.

Washington, the son of a white farmer whom he didn’t know and who didn’t care the least for his offspring, had from early childhood on the wish to get an education, to learn how to read and write and lift himself up from the conditions in which he and the other black people in the South lived. A big part of the book deals with the struggle of young Washington to achieve this goal. For years, Washington had to go through many hardships and worked in very difficult conditions as a salt miner and in other menial jobs in order to earn the required money to pay the tuition fees at school. When he finally made it to the Hampton Institute, a progressive school that gave an opportunity to many black people to get an education, Washington didn’t miss this chance and put all his energy in graduating there.

What follows is a story of hard work for a good cause: after graduating from Hampton Institute, Washington was assigned to become school principal in the newly founded Tuskegee Teachers’ School at the age of 25. He secured the support of the local people, but also of many donors in the South and the North as well (including former slave owners) by convincing them with results. The students in Tuskegee earned from the very beginning their own money in the workshops of the Institute, where they learned various professions, they erected the buildings of the fast growing school all by themselves and provided the regional market with various products in demand.

A person who makes himself useful and who is able to do something well and better than others will in the end be accepted by any community – this is the way how Washington wanted to achieve a true emancipation. Once most of the black people have a regular work and a profession or trade in which they can make a living, the relations between the races will improve as much as to make the racial prejudices and discrimination disappear – we should keep in mind that Washington published his autobiography when lynching was an everyday occurrence in most states of the South, and when more and more Southern States disfranchised the black population and withdrew the voting right from them, and when the Ku Kux Klan was at the height of its power and influence.

Washington’s approach was of course in a way naive: racism doesn’t simply disappear just because those against whom the racists discriminate (or worse) behave well, use a toothbrush – Washington is quite special about the use of the toothbrush and personal hygiene in general – and have a regular employment or learned a trade or profession that is useful to the community in which they live. On the other hand, Washington’s optimism, his clear vision and his obvious great energy and devotion to a project that really improved the lives of many people, together with his apparent skills as an orator, and his personal charm and modesty – this all opened the hearts and the purses of many people, including people like Rockefeller, Eastman or Carnegie. In the end, Washington advised Presidents, was the first black man to be awarded a honorary degree from Harvard and was received in many places like a rock star would be today.

It is quite interesting that the biggest opposition to Washington’s educational program didn’t come from white Southerners but from a faction of Washington’s “own people” in the North. Especially after his famous Atlanta Exposition Address of 1895 in which he became visible as the unchallenged leader of the black people in America, he was attacked by a faction under the leadership of W.E.B DuBois.

DuBois, who graduated in Berlin and became later the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, was initially supporting Washington, but he soon changed his opinion. According to DuBois and his supporters, Washington was too soft in his stance against violations of Civil Rights, and also his preference of industrial education over the classical liberal arts was very much to the disliking of DuBois who believed that only an elite of men educated in the liberal arts – supposedly under DuBois’ leadership – would be able to achieve social progress. It was a clash of characters from different backgrounds and very different temperaments: here the Southern man whose own education was limited as a result of his difficult life circumstances, a man with a hands-on approach to things who believes that only by self-improvement, hard work and an understanding for what is possible in the moment, the Negro race can be uplifted in the long run; on the other side, the urban, well-educated Northerner, more a politician than an educator who aspired to be the political leader of the Negro race.

As a result, Washington and DuBois had a rather complicated relationship – and while Washington is not in any way saying a bad word about his opponent in his autobiography directly, it is quite obvious to whom he is referring when he mentions a rather ridiculous example of an “educated” Negro early in his book, as someone with

“high hat, imitation gold eye-glasses, a showy walking-stick, kid gloves, fancy boots, and what not…”

In general, the autobiography gives comparatively little away about Washington’s private life. He was obviously quite a family man and seemed to have suffered at times from phases of longer separation from his wife and three children due to his extensive travelling. He lost two wives very early, but in the book he keeps his private feelings private and is not talking in detail about his grief. Whenever anyone supported him he mentions it in the book – understandable when we are aware that it was also meant as an instrument in his fundraising campaigns for Tuskegee. A previous autobiographical book published for a black audience was more critical regarding certain aspects of the life of the black community in the South and mentioned also some particular cruel examples of treatment of slaves by white slave holders, but Up to Slavery is clearly written for a white audience and possible donors; therefore these examples are omitted in the reviewed book.

All in all, the Booker T. Washington we get to know in this book was a humble and very energetic man, who achieved probably more in terms of improvement of the living conditions of the black people in the South than anyone else before or after him. That he championed industrial (i.e. vocational) training over academic training in the liberal arts, shows a much greater sense of realism than most other self-proclaimed leaders at his or later times showed, and the experiences of Tuskegee Institute can be still considered today as a good practice in the context of developing countries and communities.

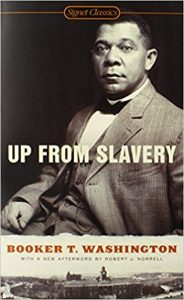

Booker T. Washington: Up from Slavery, Signet Classics, New York 2010

PS: The expressions “black people” or “Negro race” are expressions used in Washington’s book.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter